The Fantasy Adventures of Alexander the Great

I think my favorite parts of Alexander the Great’s life involve his fight with the dragon, and the time he climbed to a mountain summit and saw the angel of death. Not to mention his conversation with the speaking tree. After that, his meeting with the Emperor of China was almost superfluous.

I think my favorite parts of Alexander the Great’s life involve his fight with the dragon, and the time he climbed to a mountain summit and saw the angel of death. Not to mention his conversation with the speaking tree. After that, his meeting with the Emperor of China was almost superfluous.

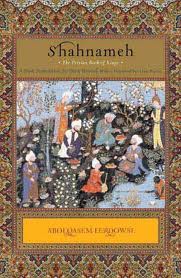

I haven’t been dropping acid. I’ve been reading from the Shahnameh, the Persian Book of Kings, an epic poem and a national treasure of Iran, written by Abolqasem Ferdowsi over the course of many decades in the 9th century O.C.E. It purports to tell the history of Persia until the time of the Arab conquest, but what it mostly does is collect fabulous tales of adventure, betrayal, war, and love centered around Persian rulers. And because Alexander the Great came to rule Persia, there’s a long section devoted to him.

Alexander the Great from history and Sekander from the Shannameh have very different lives, and the version told by Ferdowsi reads an awful lot like an abbreviated fantasy epic.

I can’t help wondering what historical sources Ferdowsi had on hand. Mostly he seems to have been working with oral tradition, and to have invented freely from there to address his favorite themes. In the real world, Alexander never penetrated very far into India. In the Shahnameh, he not only gets to India, he reaches China, not to mention a host of invented countries. Sekander, as he’s known through the Shahnameh, begins life in a similar way as he does in Western histories, complete with his brilliant tutor, Arestalis… except of course that Sekander is really the son of King Darab, father of Darius III, so that Sekander is half-brother to the Persian king he will grow up to slay.

History nerd that I am, when I first read the Shahnameh, particularly the sections with Sekander, the experience was surreal. My enjoyment was hampered by my inability to read Persian and experience the beauty and flow of the original poetry, and by my previous knowledge of the life of Alexander the Great. Yet as I became accustomed to the strangeness, I found grandeur.

History nerd that I am, when I first read the Shahnameh, particularly the sections with Sekander, the experience was surreal. My enjoyment was hampered by my inability to read Persian and experience the beauty and flow of the original poetry, and by my previous knowledge of the life of Alexander the Great. Yet as I became accustomed to the strangeness, I found grandeur.

Ferdowsi didn’t seem to have information about Alexander’s brilliant tactics, or didn’t find them of interest, for we see few real details about actual battles. What we do see is Sekander’s relentless drive to move forward and witness more of this strange and beautiful world. Time and again he pretends to be his own envoy so he can be the first to talk with a new queen or emperor. Time and again he sends forth arrogant letters to kings or queens, then conquers their lands. But Sekander is seen also to rule justly, and from time to time he stops to slay a monster, talk with interesting people, or marvel over some strange landscape. He passes by a great crystal mountain and sees a fish as large as an island. He builds a mighty wall to hold back a horde of monsters, and faces off against a fire-breathing dragon.

As he nears the end of his journey, Sekander is told more and more often that he has seen more than a fair share of marvels allotted to any man, and that his time of rule is almost through. The further Sekander pushes on, the more ominous these warnings become, until at last a heartsick Sekander returns to Babylon to die.

As in real life, the mourning for Sekander is incredible, and nearly a hundred thousand come to view his coffin, including the philosopher Arestalis and other Greek sages. But Ferdowsi allows Sekander’s mother the most powerful words:

You seemed a storm cloud charged with hail: I said

That you could never die, that you had shed

So much blood, fought so many wars, that there

Must be some secret you would not declare,

Some talisman that fate had given you

To keep you safe whatever you might do.

You cleared the world of petty kings, brought down

Into the dirt an empire’s ancient crown,

And when the tree you’d planted was to bear

Its fruits you died, and left me in despair.

A statue of Ferdowsi in the square named after him, in Tehran.

Ferdowsi himself concludes the saga with words that first struck me as bleak – and then I realized he was celebrating the power of the pen over the sword: “Sekander departed, and what remains of him now is the words we say about him. He killed thirty-six kings, but look how much of the world remained in his grasp when he died. He founded ten prosperous cities, and those cities are now reed beds. He sought things that no man has ever sought, and what remains of him within the circle of the horizon is words, nothing more. Words are the better portion, since they do not decay as an old building decays in the snow and rain.”

Ferdowsi was fascinated by the habits of a good and just ruler. Sekander is painted as a man with the instincts of justice, colored by arrogance and greedy not for gold, but the next adventure. His is a tale of philosophy shot through with vivid imagery and adventure. I was allowed entry into his world via the recent translation of the Shahnameh by Dick Davis, who gives a fascinating “behind-the-scenes” interview over at Iranian.com. Anyone remotely curious about reading the Shahnameh should visit to see Davis’s description of the work, his approach, and his favorite characters. It would be impossible to effectively translate the whole of the poem from Persian into English, which is why Dick Davis mostly converted the work into prose.

I found Sekander’s adventure, and the whole book, fascinating. Highly recommended, with my usual caveat about tales of myth and legend, east or west. Characters do not always act consistently, minor characters appear and disappear and may be poorly developed, and sometimes the thread of the story seems lost in digression over details that do not interest modern readers. It is not a book to be devoured in a couple of long sessions, but a masterpiece to be considered slowly, and revisited.

3 Comments