The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The God in the Bowl”

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story three, “The God in the Bowl.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story three, “The God in the Bowl.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: While I understand it’s a different kind of story for Conan, and that it’s interesting to look at through the lens of understanding how Howard’s writing developed, I’m evaluating each of these tales with a fairly simple agenda foremost: Do I enjoy them as stories, and do they achieve what they’re designed to do?

In this case I think both answers are no. The reasons I don’t enjoy it are closely tied to my feelings about its failure as both a mystery and a horror story. The solution is pretty well telegraphed to the reader early on, leaving it not much of a mystery. And while there is exquisitely drawn horror present, I think the story lacks the requisite tension for a horror story (as opposed to a story WITH horror).

In this case I think both answers are no. The reasons I don’t enjoy it are closely tied to my feelings about its failure as both a mystery and a horror story. The solution is pretty well telegraphed to the reader early on, leaving it not much of a mystery. And while there is exquisitely drawn horror present, I think the story lacks the requisite tension for a horror story (as opposed to a story WITH horror).

There’s also confusion about who the protagonist is — the charismatic barbarian who stands around glowering and making cool threats, and clever Demetrio, whose cleverness is so belabored it becomes irritating. Demetrio’s the only one moving the plot forward (slowly) until the stunning action scenes when Conan takes over and the story becomes interesting once more, too late.

Midway through, Robert E. Howard writes of Demetrio that: “He found these scenes wearily monotonous.” And, unfortunately, that’s how I feel about most of “The God in the Bowl.” That’s not to say it’s completely without merit, for it has finely realized horror and some great action moments, but those moments don’t make it a success. They’re like hearing one really catchy song while having to sit through a long dreary musical at your kid’s high school.

Bill: The first, almost play-like half or two-thirds of the story has Conan standing on the sidelines while other characters talk. And then yet more characters show up. I think it’s the strong final moments of “The God in the Bowl,” though, that leave readers with a better overall impression of the story.

Bill: The first, almost play-like half or two-thirds of the story has Conan standing on the sidelines while other characters talk. And then yet more characters show up. I think it’s the strong final moments of “The God in the Bowl,” though, that leave readers with a better overall impression of the story.

Howard: You’re probably right. Let me highlight what I DO like. I think it starts with strong momentum before quickly coming to a dead stop. By itself, the conclusion, beginning with the entry of the aristocrat who denies hiring Conan for the robbery, is wonderful. With his appearance we get some really snappy dialogue, then the explosion of violence between Conan and the guards, and finally the confrontation with the monster, which goes to 11 on the atmospheric and eerie scale. And Conan himself seems fully gelled — this is the unstoppable powerhouse of destruction we know and love. I’ve studied Howard fragments, rough drafts that are worth reading solely because of an amazing action sequence delivered with pulse-pounding vigor and inventiveness. You can always count on Robert E. Howard for action scenes.

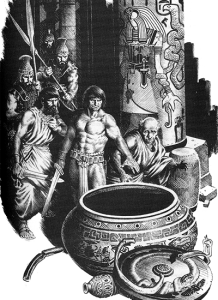

Bill: Yes, great stuff. The combat is quick and brutal and vivid — Conan even plucks a guard’s eye out for Crom’s sake — and most welcome after we’ve been standing around listening to all the talk. The Stygian Snake God, a gift from our old friend Thoth-Amon to a rival priest (I like how Conan and Thoth-Amon’s destinies seem intertwined at this point, as this encounter was just at the start of Conan’s career) is really excellent, reminding me of how a smart film director keeps his monster hidden and mysterious from the audience. Those are all my favorite moments as well, that and, as you say, a fully fleshed Conan responding to the questions and bullying of the civilized interrogators with characteristic ballsy aplomb.

Bill: Yes, great stuff. The combat is quick and brutal and vivid — Conan even plucks a guard’s eye out for Crom’s sake — and most welcome after we’ve been standing around listening to all the talk. The Stygian Snake God, a gift from our old friend Thoth-Amon to a rival priest (I like how Conan and Thoth-Amon’s destinies seem intertwined at this point, as this encounter was just at the start of Conan’s career) is really excellent, reminding me of how a smart film director keeps his monster hidden and mysterious from the audience. Those are all my favorite moments as well, that and, as you say, a fully fleshed Conan responding to the questions and bullying of the civilized interrogators with characteristic ballsy aplomb.

Also, another point, this story is Conan’s first appearance in what would become the all-time barbarian standard of dress in fantasy fiction — sandals and a loincloth!

Howard: Hah! Score one for the loincloth and sandals.

Howard: Hah! Score one for the loincloth and sandals.

It may seem I’m pretty harsh about a story written by one of my favorite writers starring one of my favorite characters, but it lacks elements of what I most love about Robert E. Howard’s writing. I think the flow is off. Usually you can count on Howard for pacing but this tale’s so drawn out that rather than feeling tension I start wondering how long it will take for the characters to get on with it.

Tension is further diluted because Conan doesn’t have much invested in the solution to the mystery — the guards are going to try to haul him away regardless. We can only watch as the man of action stands and listens to all the noise, noise, noise, noise. Demetrio thinks out loud and various bit players run in to report things that add information to what other bit players relayed. As you intimated, it’s a little like watching a dull stage play.

You could argue that I’m judging work from another time by pacing standards of our time, a mistake a lot of modern readers make when reading old adventure fiction. But this isn’t at all typical of Robert E. Howard’s style. One of the things I love about his work is that wonderful cinematic pacing, so unlike many of his predecessors and even contemporaries. If he was deliberately experimenting with a different storytelling style he inadvertently sidelined one of his greatest strengths when he did so.

Maybe if I’d read this for the first time when I was a teenager I wouldn’t have seen that conclusion coming. I can’t know — I can only react to what I first read in my 20s, and then it was clear to me from Howard’s own clues that the monster was some kind of huge-ass snake, the only (and truly creepy) surprise being its chilling face. If I focus on the horror aspect I imagine I’m supposed to feel nail-biting dread for understanding the danger that the characters do not and wondering how they can possibly survive… but that would have required me to care about more than one of them.

Maybe if I’d read this for the first time when I was a teenager I wouldn’t have seen that conclusion coming. I can’t know — I can only react to what I first read in my 20s, and then it was clear to me from Howard’s own clues that the monster was some kind of huge-ass snake, the only (and truly creepy) surprise being its chilling face. If I focus on the horror aspect I imagine I’m supposed to feel nail-biting dread for understanding the danger that the characters do not and wondering how they can possibly survive… but that would have required me to care about more than one of them.

Sorry, REH. I still think you’re awesome, I swear. I understand why Farnsworth Wright rejected this. And maybe you did too, because unlike you did with other unsold tales, you seem never to have tried revising it or sending it on to another market.

Bill: “The God in the Bowl” is similar to “The Phoenix on the Sword” in that other characters are the ones moving the plot forward, and Conan reacts to them. In both cases these are Conan vs. Civilization stories, whereas “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter” is Conan out in his own element. In none of these stories has Conan, I think, fully grown into his role as protagonist and driving force just yet — after all in “Frost-Giant” Conan is essentially bewitched. He certainly isn’t making choices. Looking at just “God” and “Phoenix,” it almost seems to me that REH needed to focus on the civilized players and their plots as a way of finding out who Conan was in contrast. After these first three tales, though, Conan is firmly in the driver’s seat for much of the rest of his stories.

Howard: In later stories Howard sets events in motion by showing us what’s under way before Conan wanders in and upsets the apple cart. I suppose that kind of happens here, but not in an especially interesting way. I wish he had rewritten it to trim it down, lengthwise, because the conclusion rocks, and there are several nice touches throughout — the cable that we readers are rightly suspicious of, various small character-revealing asides, and so on. Yes, there are good character moments, but I still didn’t find these other players compelling enough to watch them take center stage for so long.

Howard: In later stories Howard sets events in motion by showing us what’s under way before Conan wanders in and upsets the apple cart. I suppose that kind of happens here, but not in an especially interesting way. I wish he had rewritten it to trim it down, lengthwise, because the conclusion rocks, and there are several nice touches throughout — the cable that we readers are rightly suspicious of, various small character-revealing asides, and so on. Yes, there are good character moments, but I still didn’t find these other players compelling enough to watch them take center stage for so long.

Bill: I think we can both pretty easily imagine a better version of this story, no reason not to point out its flaws. I think the pacing issue becomes even more telling upon rereading, because there isn’t even the curiosity about the ending to supply interest. But from this point forward things change, Conan and REH hit their stride, and some immortal sword-and-sorcery stories start flying off the Underwood — next week’s “The Tower of the Elephant” shall be the first of many!

23 Comments