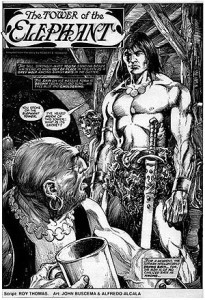

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The Tower of the Elephant”

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story four, “The Tower of the Elephant.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story four, “The Tower of the Elephant.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: If you listen very closely, toward the end of the final verse of The Beatles hit “Hey Jude” you can hear either Lennon or McCartney (stories vary) shout out in surprise “Whoa!” followed a moment later by “f*ing Hell!” Once you notice it, you can never NOT hear it, a single small ding in an otherwise flawless song. I feel the same way about Robert E. Howard’s use of the word “frostily” or “frosty” in “The Tower of the Elephant.” I didn’t notice it the first four or five times I read the tale. Now I can’t ever NOT see that he uses it maybe two times too many.

And damned if that tiny nitpick isn’t the only thing I can find remotely wrong with this story. THIS is Robert E. Howard at his absolute best, in complete control of his narrative, knowing his character better than his closest friend. His Hyborian history article was written just prior to his penning of “The Tower of the Elephant,” which makes sense, because he knows the history and societies so well that he casually mentions cultures in such a way we can usually intuit what he’s talking about.

And damned if that tiny nitpick isn’t the only thing I can find remotely wrong with this story. THIS is Robert E. Howard at his absolute best, in complete control of his narrative, knowing his character better than his closest friend. His Hyborian history article was written just prior to his penning of “The Tower of the Elephant,” which makes sense, because he knows the history and societies so well that he casually mentions cultures in such a way we can usually intuit what he’s talking about.

Bill: Yes, you can really see him drawing on some of that background he had just worked out in this story, both in the cosmopolitan setting, and in the bit of “deep history” he gives us in the words of the Elephant God toward the story’s close.

Howard: Yeah — now I’m glad you insisted we read that essay first.

I love the opening of this story. I keep comparing Robert E. Howard’s description to camera work, because he often uses an establishing shot. His words present the hustle and bustle and atmosphere of both the section of the city and the tavern itself.

I love the opening of this story. I keep comparing Robert E. Howard’s description to camera work, because he often uses an establishing shot. His words present the hustle and bustle and atmosphere of both the section of the city and the tavern itself.

And then Conan appears. We, the readers, know well who he is, even though he’s not mentioned by name, and he clearly dominates the scene. And, true master that he is, REH continues to give us great throw away lines that are incredibly revealing of character: “The Cimmerian glared about, embarrassed at the roar of mocking laughter that greeted this remark. He saw no particular humor in it, and was too new to civilization to understand its discourtesies. Civilized men are more discourteous than savages because they know they can be impolite without having their skulls split, as a general thing.”

Bill: Here Conan is a “gray wolf among gutter rats,” to paraphrase just one of the great lines in the opener. From the first paragraph of this section that paints a vivid picture of The Maul, the thieves district of Zamora where the guards have been bribed with “stained coins” to leave the criminals alone, all the way to the conclusion, which sees Conan slay the civilized man who just didn’t understand that you can only push some men — literally in this case — so far. I think this opener, and this story in general, is one of the best introductions to Conan, and probably the one I would hand a novice that was interested in seeing what all the fuss is about.

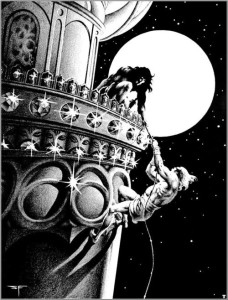

Howard: Me too — this is usually where I tell people to start. A great story like this is chock full of one fine scene after another, and we next get Conan’s take on civilized religion, then join him for his foray into the grounds of the Tower of the Elephant. The action is fluid and surprising and exciting. The meeting with Taurus and the thief’s astonishment at his daring is perfect. At first it seems like Conan is outclassed, but then he lengthens the thief’s life by slaying that lion, impressing both him and the readers at the same time.

Howard: Me too — this is usually where I tell people to start. A great story like this is chock full of one fine scene after another, and we next get Conan’s take on civilized religion, then join him for his foray into the grounds of the Tower of the Elephant. The action is fluid and surprising and exciting. The meeting with Taurus and the thief’s astonishment at his daring is perfect. At first it seems like Conan is outclassed, but then he lengthens the thief’s life by slaying that lion, impressing both him and the readers at the same time.

Bill: It’s Conan’s savage instincts that ultimately prove to be of greater worth than Taurus’ long experience. Even a Prince of Thieves — a man with a poison gas blowgun, super-rope, and a strangler’s grip — doesn’t have eyes in the back of his head like a barbarian who has lived by his wits in wild places. And the whole interaction between the two is really finely put together, just trying to imagine the story without Taurus results in something lesser. As amazing as Taurus is, it’s Conan that, as you say, we ultimately become even more impressed with, and that’s only because we have Taurus to compare him to.

Howard: Right on all counts. Taurus allows us to better understand how impressive Conan is, and I can’t imagine the story being as enjoyable without him. The tower itself is gorgeous. I still wonder what Taurus planned when he told Conan to remain behind, the characters being so well motivated that I don’t find myself asking what REH intended, but what his character was thinking. Hocking and I were talking about it the other week and we were both wondering whether or not Taurus was going to betray Conan, or if he actually had something in mind for him to do.

Howard: Right on all counts. Taurus allows us to better understand how impressive Conan is, and I can’t imagine the story being as enjoyable without him. The tower itself is gorgeous. I still wonder what Taurus planned when he told Conan to remain behind, the characters being so well motivated that I don’t find myself asking what REH intended, but what his character was thinking. Hocking and I were talking about it the other week and we were both wondering whether or not Taurus was going to betray Conan, or if he actually had something in mind for him to do.

Bill: Right, I’m not sure either. Taurus has already established he knows a good deal that Conan does not, not just of thievery in general (the discussion about why you would leave a dead guard’s body out rather than hide it was a small slice of brilliance) but of the Tower in particular. So, when he dashes ahead of Conan there is enough doubt established to suggest that maybe he really is working in both their interests. I would suggest, though, that in every other instance of Conan’s instincts in this story Conan is reacting accurately, he does not “doubt his senses” even when confronted with the impossibility of the Elephant God himself, as a civilized man would. And Conan’s initial reaction to Taurus’s entering the tower while Conan does a possibly needless bit of scouting was to distrust the Nemedian’s intentions.

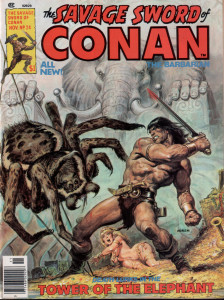

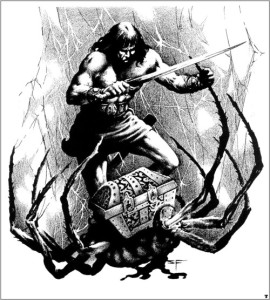

Howard: And damn, there are giant spider fights, and then there’s the fight with the thing in the top room of the tower. The only giant spider fight I’ve read that’s on the same level is the one from the first Bard book by Keith Taylor. You can see this monster and its dripping venom, so virulent that it scars Conan for life. And it’s not just a swing and a miss and a squish, that dammed thing stalks him and scuttles across the ceiling. It’s just incredibly well written, so much so that even after reading this story multiple times I still find it thrilling. And unsettling.

Howard: And damn, there are giant spider fights, and then there’s the fight with the thing in the top room of the tower. The only giant spider fight I’ve read that’s on the same level is the one from the first Bard book by Keith Taylor. You can see this monster and its dripping venom, so virulent that it scars Conan for life. And it’s not just a swing and a miss and a squish, that dammed thing stalks him and scuttles across the ceiling. It’s just incredibly well written, so much so that even after reading this story multiple times I still find it thrilling. And unsettling.

Bill: The fight is great, and it’s also interesting how clever the spider is — the move it used to bind Conan’s ankle was very slick. Really, the only things that come close to killing Conan in this story are creatures operating at an even more instinctual level than himself.

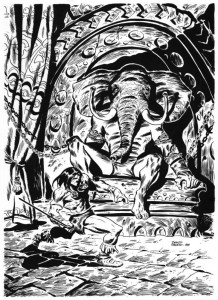

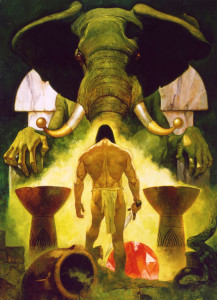

Howard: Right! Finally we arrive at the big reveal, with one of my favorite moments not just from Robert E. Howard or his Conan stories, but all adventure fiction, when Conan comes upon the crippled creature:

“…and Conan’s gaze strayed to the limbs stretched on the marble couch. And he knew the monster would not rise to attack him. He knew the marks of the rack, and the searing brand of the flame, and tough-souled as he was, he stood aghast at the ruined deformities which his reason told him had once been limbs as comely as his own. And suddenly all fear and repulsion went from him, to be replaced by a great pity. What this monster was, Conan could not know, but the evidences of its sufferings were so terrible and pathetic that a strange aching sadness came over the Cimmerian, he knew not why. He only felt that he was looking upon a cosmic tragedy, and he shrank with shame, as if the guilt of a whole race were laid upon him.”

“…and Conan’s gaze strayed to the limbs stretched on the marble couch. And he knew the monster would not rise to attack him. He knew the marks of the rack, and the searing brand of the flame, and tough-souled as he was, he stood aghast at the ruined deformities which his reason told him had once been limbs as comely as his own. And suddenly all fear and repulsion went from him, to be replaced by a great pity. What this monster was, Conan could not know, but the evidences of its sufferings were so terrible and pathetic that a strange aching sadness came over the Cimmerian, he knew not why. He only felt that he was looking upon a cosmic tragedy, and he shrank with shame, as if the guilt of a whole race were laid upon him.”

It was a habit of the times to give villains monologues, or to explain plot points through sages. We’ve seen that already in some Leiber, most especially the dreadful “Adept’s Gambit” and we’ve seen a little of it in preceding Conan stories. We’ll see it in some written after. But THIS monologue is so nicely done that it flows naturally, and the moment is so riveting that we can imagine Conan standing, nearly spellbound, considering it.

Bill: And the cosmic stranger’s plight is the strongest condemnation of civilization in the story, going right back to that theme that was there from the start. The vile man who has tortured the creature for its secrets is not described as a magician or sorcerer, but a priest — in the fact the High Priest of the city, a man whom the ruler of Zamora fears and obeys. A barbarian thief might cut your throat, but he won’t enslave and torture you for centuries to get at forbidden knowledge. The tower that is the Elephant God’s prison was built with his own stolen power, a very constructive, civilized use of such magic. In the end, it’s a fellow-outsider who does not flinch away from the impossible visitor from the planet Yag, who clearly sees the misuse the creature has been put to, and who kills it for the sake of mercy and of vengeance. It did occur to me that Conan’s obeying of the Elephant God’s final wishes may be due to some geas laid on the Cimmerian, his revulsion and sense of justice possibly not being enough of a motivation to risk everything to confront the priest. I suppose, at that point, Conan’s only way out was to do as the creature bade him, so it isn’t as if he had any real options, anyway.

Bill: And the cosmic stranger’s plight is the strongest condemnation of civilization in the story, going right back to that theme that was there from the start. The vile man who has tortured the creature for its secrets is not described as a magician or sorcerer, but a priest — in the fact the High Priest of the city, a man whom the ruler of Zamora fears and obeys. A barbarian thief might cut your throat, but he won’t enslave and torture you for centuries to get at forbidden knowledge. The tower that is the Elephant God’s prison was built with his own stolen power, a very constructive, civilized use of such magic. In the end, it’s a fellow-outsider who does not flinch away from the impossible visitor from the planet Yag, who clearly sees the misuse the creature has been put to, and who kills it for the sake of mercy and of vengeance. It did occur to me that Conan’s obeying of the Elephant God’s final wishes may be due to some geas laid on the Cimmerian, his revulsion and sense of justice possibly not being enough of a motivation to risk everything to confront the priest. I suppose, at that point, Conan’s only way out was to do as the creature bade him, so it isn’t as if he had any real options, anyway.

Howard: Oh, I’m pretty sure he does it out of choice, that he senses the truth of what the creature has told him. I think at least that’s what REH is wanting us to think. We, the reader, are just as convinced as Conan has been.

Howard: Oh, I’m pretty sure he does it out of choice, that he senses the truth of what the creature has told him. I think at least that’s what REH is wanting us to think. We, the reader, are just as convinced as Conan has been.

Bill: As am I, really, there’s just that one line, about it not even occurring to Conan not to follow instructions, that had me thinking that maybe there’s a small case to be made for the Elephant God pulling a few strings, but it’s certainly more subtle (subtle to the point that it’s probably solely in my imagination) than anything in “Frost-Giant’s Daughter.” I like that that ambiguity can crop up though, even if it isn’t intended at all, because REH isn’t beating the reader over the head by telegraphing Conan’s intentions. It says something that a penniless wanderer would forego a priceless treasure in order to avenge a monstrous crime — a crime against a creature far more alien than any lion, spider, or civilized man.

Howard: Yeah. There’s a certain elemental decency about Conan that gets overlooked, or exaggerated.

Bill Overall, this is a story that does everything right, and does it masterfully. Conan is the man we will come to know in future tales, the Hyborian landscape has been delineated in a way that deftly integrates it into the story, and the action and imagination hooks the reader and carries them right along to the finish. It seems pretty simple, too, until you go back and look at how the pieces fit together — and then you realize it only seems simple because it was crafted with an expert hand. It’s one of the best of the best, and its no surprise that “The Tower of the Elephant” is a perennial fan favorite.

Bill Overall, this is a story that does everything right, and does it masterfully. Conan is the man we will come to know in future tales, the Hyborian landscape has been delineated in a way that deftly integrates it into the story, and the action and imagination hooks the reader and carries them right along to the finish. It seems pretty simple, too, until you go back and look at how the pieces fit together — and then you realize it only seems simple because it was crafted with an expert hand. It’s one of the best of the best, and its no surprise that “The Tower of the Elephant” is a perennial fan favorite.

Howard: It’s certainly one of mine. But then I’m a fan. Next week, join us for a journey to “The Scarlet Citadel.”

30 Comments