The Liberation: An Interview with Ian Tregillis

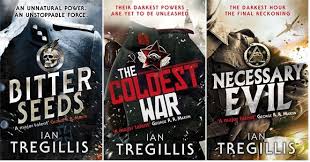

Last year I sat down with Ian Tregillis over at Black Gate to discuss his new book. Tregillis is one of the few modern writers I go out of my way to read, and I think my regular readers would really enjoy him.

Here’s a reprint of that discussion:

As John O’Neill wrote in November of 2016, the last book in Ian Tregillis’ new trilogy comes out this month (December 2016). I’m a big fan of Tregillis, and was fortunate enough to read The Liberation in manuscript. It was a blast, and you should buy it it. Seriously. Go buy the trilogy, and if you already have the first two, go buy the third.

Alright. Now that you’ve done that, Ian and I kicked back last and talked about his trilogy. Here’s what he had to say:

Howard: You’re on an elevator with your new book when Ringo Starr enters, sees the cover and says how fab it looks. He wants to know what the book’s about – what do you tell him?

Ian: OK. First of all, I’d probably be hard pressed not to lose my composure the moment he stepped into the elevator. I mean, there I’d be sharing an  elevator with A BEATLE. I discovered their albums at just the right age, and I swear I listened to that music practically nonstop during high school. So keeping it cool would be a challenge, *especially* if Ringo asked about the book.

elevator with A BEATLE. I discovered their albums at just the right age, and I swear I listened to that music practically nonstop during high school. So keeping it cool would be a challenge, *especially* if Ringo asked about the book.

But assuming I could recover my composure enough to speak coherently without babbling, and assuming he wanted the long version, I’d tell him it’s an adventure story about a clockpunk Terminator apocalypse in a world where the industrial revolution never happened, disguised as a story about slave rebellion and Free Will.

If he wanted the short version, I’d tell him it’s basically Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots but with more swearing and stabbing.

Speaking of those robots, what interested you in mechanical men, and how did you come upon the particular time period and circumstances? I don’t imagine it was simply a matter of “well, THIS has never been done before.” I mean, it’s not just steampunk, it’s set in an alternate history that diverges in a very different place, and gives power to the Dutch.

Speaking of those robots, what interested you in mechanical men, and how did you come upon the particular time period and circumstances? I don’t imagine it was simply a matter of “well, THIS has never been done before.” I mean, it’s not just steampunk, it’s set in an alternate history that diverges in a very different place, and gives power to the Dutch.

Back when I was writing the Milkweed Triptych (and, oddly, continuing with the theme of my evolving musical tastes) I stumbled across the music of Abney Park, which had just undergone its transition from goth to steampunk. I listened to a lot of their music after that, and found many of their songs sparking story ideas for me. I kept flashing back to this fascinating image of clockwork men and women, and eventually developed a pretty solid sense that I’d like to wrap a book around that conceit.

Some time after that, around 2010 or 2011, I was invited to contribute a story to an anthology titled, “Human for a Day.” I decided to use that story as a playground for exploring the clockwork-person idea. I had a vague notion the short story would be about a clockwork robot trying to find a secret locksmith who could pick the lock on his imprisoned soul, but I really didn’t know anything about the world around him. And I needed a setting before I could start writing the anthology piece.

I decided the easiest and most natural piece of worldbuilding would be terminology for the clockwork servitors. If they were common in this world, there’d be slang terms for them. Furthermore, I reasoned, if they were basically walking clocks, they’d be loud, and the resulting slang might be onomatopoeic. So then I started doodling at the keyboard, trying to invent a word that evoked the sound of a mechanical slave going about its business. Nothing really landed until I hit “clakker”. Who knows why, but for some reason that made me think of Dutch (a language I don’t speak), at which point my brain lit up.

I knew from the science side of my life that Christiaan Huygens had been a Dutch mathematician/ astronomer/ early physicist, and an inventor of the pendulum clock. I also knew he’d been a contemporary of Isaac Newton, and that Newton had been deeply into alchemy. Well, gosh: what if, centuries earlier, Huygens had stolen Newton’s alchemical research, combined it with horology, and invented sentient clockwork slaves? This would have been right around the time that Catholic Louis XIV of France had invaded the Protestant Netherlands, too, and not terribly long before the Dutch would eventually give up the city of New Amsterdam…

I knew from the science side of my life that Christiaan Huygens had been a Dutch mathematician/ astronomer/ early physicist, and an inventor of the pendulum clock. I also knew he’d been a contemporary of Isaac Newton, and that Newton had been deeply into alchemy. Well, gosh: what if, centuries earlier, Huygens had stolen Newton’s alchemical research, combined it with horology, and invented sentient clockwork slaves? This would have been right around the time that Catholic Louis XIV of France had invaded the Protestant Netherlands, too, and not terribly long before the Dutch would eventually give up the city of New Amsterdam…

In an instant, I had an entire new world in my head. That’s a really great (but unfortunately for me, rare) feeling for a writer.

So that became the setting for the story. But I knew instantly that the world was too big and complex for 7,000 words. It deserved its own book. Later, Orbit convinced me that it was really too big for a single book, and that it deserved several. They were right. (Oddly, the Milkweed Triptych *also* grew out of people convincing me, correctly, that my idea was too big for a single book.)

That’s a somewhat lengthy answer to your question, but there you go.

I always like hearing the background details behind creative projects — well, at least the ones I’ve enjoyed. Often, the ideas I like most are ones that spring from the random confluence of several seemingly unrelated concepts. One of the things I love about your writing is how compelling it is even as it mixes those concepts around. Do you take any conscious steps to keep that plot continually tugging the reader forward?

That’s one of the best compliments a writer can receive, so thank you sincerely for that. I’ll tell you honestly, it never feels compelling when I’m writing it. I tend to get bored pretty easily, in fact, so I’m constantly looking for ways to keep things personally interesting. Otherwise the writing can become a deadly slog. I suppose that means I’m also trying to look at what I’ve written from a reader’s perspective, and worrying about how dull it’s getting.

That’s one of the best compliments a writer can receive, so thank you sincerely for that. I’ll tell you honestly, it never feels compelling when I’m writing it. I tend to get bored pretty easily, in fact, so I’m constantly looking for ways to keep things personally interesting. Otherwise the writing can become a deadly slog. I suppose that means I’m also trying to look at what I’ve written from a reader’s perspective, and worrying about how dull it’s getting.

I’ve found that when a scene is giving me trouble, it’s sometimes because I’m approaching it in a way that isn’t engaging my interest. When I notice that happening, I step back and ask myself, “What’s being accomplished by this scene? Do I really need this scene? What’s a more original or more interesting way to approach this? What can I put into this scene that would make it fun to write?” Sometimes the best question to ask myself is, “If I were reading this book instead of writing it, what would keep me going a little longer?”

Sometimes that’s just a matter of juicing up the dialogue. Or discovering a character’s voice. Or revealing some nifty corner of the world. Or teasing a revelation. Or letting somebody get stabbed in the eye. You know, whatever.

I know we share a love of the works of Zelazny and Chandler. Very different writers, obviously, but I think I’ve detected a common thread that explains why I find their work so compelling: the element of surprise. With Chandler, it’s the constant thrills delivered by his spectacular and unpredictable prose. Never knowing what ingenious turn of phrase will hit me next more than makes up for plotting and characterization that’s a little predictable at times. With Zelazny, it’s not only surprising prose but also surprising worldbuilding, surprising storytelling. I call this the “fractal dimensionality of surprise” and could deliver a 20 minute speech outlining my theory (I have, in fact) but I’ll spare you.

I’ll never be a Zelazny or a Chandler, but I can at least learn from them. So I try to keep things surprising, in large ways and small.

None of can ever be another Zelazny or Chandler, although many of us can try. My guess is that sooner or later some of us will be trying to write like Ian Tregillis, and probably want to know details like those asked by certain prescient interviewers. For instance, how long were you working on the Alchemy Wars books? Is this a long germinating idea, or one that burst fully formed that demanded you start work on it immediately?

None of can ever be another Zelazny or Chandler, although many of us can try. My guess is that sooner or later some of us will be trying to write like Ian Tregillis, and probably want to know details like those asked by certain prescient interviewers. For instance, how long were you working on the Alchemy Wars books? Is this a long germinating idea, or one that burst fully formed that demanded you start work on it immediately?

That revelation about the world I described earlier happened not long after I finished the Milkweed Triptych. But at that point I’d already promised myself that I’d write Something More Than Night, my angel-noir Raymond Chandler pastiche (I wouldn’t claim it rises to the level of homage), a project I’d been itching to tackle for years. So Clakkers went on the back burner for a year or two. But they came back when I started casting about for a new project after finishing the angel book.

Once I actually started the Alchemy Wars books, it was a little over 4 years from typing “Chapter 1” in the first draft of The Mechanical to the release of the third and final novel, The Liberation. About 3 and a half years of actively working on the books, I suppose. I’m not a screamingly fast writer.

What’s next for Ian Tregillis?

No robots, that’s for damn sure.

I do have an idea I’m playing with right now, but it’s too early to discuss it publicly. Right now I’m just trying to see if I can nurture it into something that wants or deserves to be a book. I’m excited about the concept, but it’ll require a substantial departure from the writing process that served me over the past 7 books. And who knows– even if I do write it, there’s no guarantee anybody will want to publish it!

What do you want people to find in your works, best case scenario?

What do you want people to find in your works, best case scenario?

I just hope people find some entertainment in my books! That’s the only reason I write, after all — to entertain myself.

Which of your characters from these books would you most like to sit down with for a casual conversation, and why? I think I’d vote for Jax, myself. He seems pretty gear, as Ringo might say.

I see what you did there.

I’d hate missing the chance to witness a walking, talking, sentient clockwork person. So, yeah, I guess Jax. I mean, he’s probably the safest choice from among the Clakkers…

Although, to be perfectly honest, he was never the most interesting character to write. He’s central to the story — the books had to have a Jax character — but his scenes were rarely fun to write. Instead, it was Berenice who leapt from the page the moment I first envisioned her dangling over the fortress walls of Marseilles-in-the-West, dolled up in a Marie Antoinette getup with a torch in hand, studying a clockwork killer.

Yeah. I’d like to go out for drinks with Berenice.

She’s clever, dangerous, brilliant, and sexy. A happily married man like me should probably steer clear. I should say, though, that while those scenes may have been hard to write, they worked wonderfully. Jax proved engaging and sympathetic. But that’s part of the mystery of writing, isn’t it? That if we do write properly, no one can tell whether a scene was an incredible challenge or popped off polished in a single draft. I wish the latter happened more often.

She’s clever, dangerous, brilliant, and sexy. A happily married man like me should probably steer clear. I should say, though, that while those scenes may have been hard to write, they worked wonderfully. Jax proved engaging and sympathetic. But that’s part of the mystery of writing, isn’t it? That if we do write properly, no one can tell whether a scene was an incredible challenge or popped off polished in a single draft. I wish the latter happened more often.

Well, thank you for the reassurance. I’m glad I didn’t kill him off back in the first book of the trilogy, which I’d been tempted to do…

I think you’re right on the money. If we do our jobs properly, the background struggles should be invisible to the reader. I consider rewriting part of the writing process — it’s really where a lot of the heavy lifting is done, at least for me. I often say (because I know it to be true) that I’m a far better rewriter than writer. Rewriting is, I think, where the really uncooperative scenes get sanded down and smoothed to fit seamlessly (one hopes) with the less obstreperous ones.

One of the most helpful pieces of writing wisdom I’ve come across, originally from Gaiman, goes something like this (paraphrased like mad): Some days the writing is easy. Sometimes it’s extremely difficult. But when it’s all said and done, readers won’t necessarily know which bits were easy and which bits were hard. I take great solace in that.

Thanks for taking the time for our virtual sit-down!

It was my pleasure. Thanks for the opportunity!

1 Comment