Conan Re-Read: “Beyond the Black River”

Bill Ward and I are reading through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Conquering Sword of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Beyond the Black River.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are reading through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Conquering Sword of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Beyond the Black River.” We hope you’ll join in!

“Barbarism is the natural state of mankind,” the borderer said, still starring somberly at the Cimmerian. “Civilization is unnatural. It is the whim of circumstance. And barbarism must ultimately triumph.”

Bill: So concludes “Beyond the Black River,” a story that might almost be REH’s thesis on his philosophy of civilization. It is a story that introduces new elements to Conan’s world, demonstrating again how flexible and expandable REH’s Hyborian blueprint was even after sixteen complete short (and not so short) stories and a novel. But it also maintains a continuity with what has come before, giving us perilous adventure with supernatural antagonists and, of course, Conan being Conan.

Howard: I think it builds nicely on what we’ve seen before. As it happens, though, it’s not exactly a great introduction to Conan himself, or even the Hyborian Age. It was the first Conan story I was ever handed to read, and I bounced right off of it, delaying my engagement by the world of Conan and the writing of Robert E. Howard for at least three more years, and I have forever after shaken my head at the wisdom of the person who handed me this tale to start with. It’s very different from the preceding Conan stories, feeling very much like a tale of Indian warfare, and Conan himself, while busy doing incredible things, is almost a secondary character.

Howard: I think it builds nicely on what we’ve seen before. As it happens, though, it’s not exactly a great introduction to Conan himself, or even the Hyborian Age. It was the first Conan story I was ever handed to read, and I bounced right off of it, delaying my engagement by the world of Conan and the writing of Robert E. Howard for at least three more years, and I have forever after shaken my head at the wisdom of the person who handed me this tale to start with. It’s very different from the preceding Conan stories, feeling very much like a tale of Indian warfare, and Conan himself, while busy doing incredible things, is almost a secondary character.

Bill: Agreed, this story is more of a culmination of the series, really almost the opposite of an introduction. I think you have to already know the Cimmerian, as well as REH’s ongoing theme, to appreciate the best the story has to offer. The background for “Beyond the Black River” is nicely described in the third part of Patrice Louinet’s ever-excellent Hyborian Genesis essay in the back of the Del Rey and Wandering Star editions of the complete Conan stories. REH’s interests had taken him away from the ancient and medieval world and toward a desire to celebrate and explore the stories of his own country — in particular those of the American frontier. But, in addition to this new element, REH also reaches back to one of his oldest obsessions and gives us the Picts, whom we have not yet encountered in Hyboria, fusing them into a kind of amalgam of the historical and fantastical Picts of his own previous tales of Kull and Bran Mak Morn, and the Native American tribal antagonists of the frontier. The result are the purest barbarians yet presented in a Conan tale, aside from the Cimmerian himself.

Howard: Right. And the story itself is perhaps the most barbaric of any in the entire Conan canon, with the most quoted phrase about barbarism that Robert E. Howard ever wrote.

Howard: Right. And the story itself is perhaps the most barbaric of any in the entire Conan canon, with the most quoted phrase about barbarism that Robert E. Howard ever wrote.

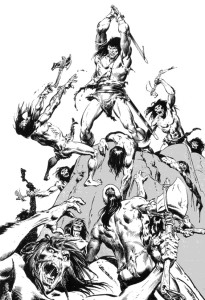

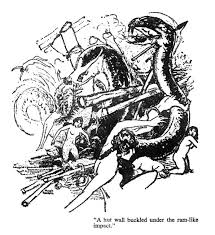

Bill: Against this barbaric Pictish frontier the civilized men of Aquilonia encroach with forts and colonies. Our protagonist, Balthus, is one such man — a civilized man who is no effete urban decadent, but a man of the woods and fields. Immediately upon being introduced to Balthus he is saved from a Pictish ambush by Conan, an ambush he never sees or even suspects. It is the first contrast of many in the tale between the civilized man and the pure barbarian. A little later Conan leads a small group of his best fighters against the Picts and all save the Cimmerian are lost — those fighters, hard men of the frontier, are none-the-less of the blood of civilized races. Conan, and the Picts, are barbarians of a thousand generations, men with the unerring instincts of wild animals. The rough men of the frontier can only adapt so far to such an existence.

Balthus, as our primary point of view character, allows REH to use a tried and true technique — viewing the Cimmerian through the eyes of another. In past tales this was most often done via a damsel in distress. In “Beyond the Black River,” however, REH is not simply serving up Conan’s barbarism as characterization, but as part of the fundamental theme of the story. It is necessary to make the point that such a frontier existence, like that found in America for much of its history, exerts a change on civilized men — but that such a change only goes so far. Conan, and men like him, are not made, they are born. Slasher, a dog that has gone nearly feral after the death of his master, is a metaphor for this — and he dies alongside Balthus, heroically and out of loyalty (he after all chooses to follow the civilized man, and not the barbarian), whereas Conan survives. Conan always survives — the barbarian always triumphs.

Balthus, as our primary point of view character, allows REH to use a tried and true technique — viewing the Cimmerian through the eyes of another. In past tales this was most often done via a damsel in distress. In “Beyond the Black River,” however, REH is not simply serving up Conan’s barbarism as characterization, but as part of the fundamental theme of the story. It is necessary to make the point that such a frontier existence, like that found in America for much of its history, exerts a change on civilized men — but that such a change only goes so far. Conan, and men like him, are not made, they are born. Slasher, a dog that has gone nearly feral after the death of his master, is a metaphor for this — and he dies alongside Balthus, heroically and out of loyalty (he after all chooses to follow the civilized man, and not the barbarian), whereas Conan survives. Conan always survives — the barbarian always triumphs.

Howard: On re-reading this, I was surprised by how late Slasher turns up in the story. I had recalled that he was Balthus’ companion and misremembered that he was there from the start.

Bill: Here, the triumph is hollow. It’s only Conan’s person that survives intact, and he himself does not care about the larger ramifications of the loss of the territory on the other side of Thunder River. Indeed, he is pessimistic, and sees all too clearly what will happen. He himself was once a barbarian laying waste to an outpost of civilization at Venarium. Conan fights out of his own sense of honor and out of personal loyalty and respect, and he certainly prefers the Aquilonian colonists to the debased and wholly-savage Picts, but he only feels the losses endured by the colonists on a personal level; the larger horror of civilization being razed in fire and blood does not touch his mind. It’s this oblivious and yet adamant survival instinct that so stuns the woodsmen in the final passage of the story quoted above. Conan suffers no psychic wounds from the reversal, instead he guzzles wine and honors the fallen with a “heathen” ablution and vows to take heads in their honor — just as the vile Zogar Sag collected heads for his own revenge. The borderer realizes Conan is more akin to the savage enemies he has just faced, than he ever could be to the men who have just fallen in defense of the frontier.

Bill: Here, the triumph is hollow. It’s only Conan’s person that survives intact, and he himself does not care about the larger ramifications of the loss of the territory on the other side of Thunder River. Indeed, he is pessimistic, and sees all too clearly what will happen. He himself was once a barbarian laying waste to an outpost of civilization at Venarium. Conan fights out of his own sense of honor and out of personal loyalty and respect, and he certainly prefers the Aquilonian colonists to the debased and wholly-savage Picts, but he only feels the losses endured by the colonists on a personal level; the larger horror of civilization being razed in fire and blood does not touch his mind. It’s this oblivious and yet adamant survival instinct that so stuns the woodsmen in the final passage of the story quoted above. Conan suffers no psychic wounds from the reversal, instead he guzzles wine and honors the fallen with a “heathen” ablution and vows to take heads in their honor — just as the vile Zogar Sag collected heads for his own revenge. The borderer realizes Conan is more akin to the savage enemies he has just faced, than he ever could be to the men who have just fallen in defense of the frontier.

Howard: It’s a powerful and rather subtle sentiment despite its violence, and it should be a moving tale — and yet I have to confess that it has always left me a little cold. Perhaps I shouldn’t ever say that in public, because I know many Conan fans name it as among the best. I recognize that it’s one of the most important, and the one where REH says most directly what he wants to say about barbarism, but, as I mentioned above, I bounced completely off of the story the first time I read it, being so disenchanted that I didn’t try any more Conan for years. Even after I’d embraced the writing of REH, when I read “Beyond the Black River” a second time I still wasn’t wowed, and here, upon the third read, while I may be capable of appreciating its technical aspects, I’m still not enthralled.

I’m struggling to give voice to why that is. Usually I can be more articulate about these things. I can guess that my reaction stems from several elements: I miss a stronger weird element, I would rather the story feature Conan… but in the end that doesn’t add up to enough to evoke my sour expression when I finish. I really ought to enjoy it more than I do. It’s well paced, it’s well plotted, it’s crammed with action. Conan gets to do some amazing things, and our protagonist rises to prove himself. And it’s got a cool dog character. Yet there were no places where the story held me spellbound with stunning prose or astonishing world building. As with the first and second time reading it, I struggled to maintain interest until I got to the end. It felt more like I’d finally run past the finish line, flagging and tired, than that I’d reached the end of an exhilarating roller coaster ride.

Bill: I think I can guess at a few reasons why that might be. For a start, the story is rather grim and pessimistic. That element can be found to a greater or lesser extent in many Conan tales, but here it is the focus and culmination of the story. This is not the heroic celebration of a strong free man’s victory against all odds, but rather a look the ugliness of a life and death struggle. Our primary protagonist dies — heroically, but not gloriously or victoriously. Conan, held at arm’s length for much of the story, is seen to be as much of an alien to the people he was protecting as the savage Picts that are their enemies. In short, it isn’t a fun story, and it ends with a real downer.

Bill: I think I can guess at a few reasons why that might be. For a start, the story is rather grim and pessimistic. That element can be found to a greater or lesser extent in many Conan tales, but here it is the focus and culmination of the story. This is not the heroic celebration of a strong free man’s victory against all odds, but rather a look the ugliness of a life and death struggle. Our primary protagonist dies — heroically, but not gloriously or victoriously. Conan, held at arm’s length for much of the story, is seen to be as much of an alien to the people he was protecting as the savage Picts that are their enemies. In short, it isn’t a fun story, and it ends with a real downer.

I think it’s a great story, though, and rank it perhaps just shy of the best tales in the series, but the strongest elements in “Black River” are the thematic ones; in terms of pace, language, setting, invention, and character you will find better yarns in earlier pieces. As you say, it doesn’t work well as an introduction. For established fans of Conan, and especially of REH as a writer, “Black River” does new things and says new things, or at least says them in a different way, and it works far better than REH’s earlier attempt to do something similar in “The Vale of Lost Women.”

“Black River’s” unvarnished look at savagery and human nature and its downbeat ending make it a lot less enjoyable than something like “Black Colossus” or “The Tower of the Elephant,” but I think it also indicates the sincerity and seriousness of REH and his approach to the life of Conan. Many creators of a series character may have moved into a decadent or near-parody direction after so many stories, and indeed REH himself had cracked a Conan “formula” late in his initial foray into the character with tales like “Iron Shadows in the Moon.” But REH kept innovating, kept caring about his creation and using Conan and Hyboria as a lens to tell different kinds of stories. It’s extraordinary when you consider the sheer variety represented within the Conan canon, as pure a testament as any to the restless genius of its creator.

“Black River’s” unvarnished look at savagery and human nature and its downbeat ending make it a lot less enjoyable than something like “Black Colossus” or “The Tower of the Elephant,” but I think it also indicates the sincerity and seriousness of REH and his approach to the life of Conan. Many creators of a series character may have moved into a decadent or near-parody direction after so many stories, and indeed REH himself had cracked a Conan “formula” late in his initial foray into the character with tales like “Iron Shadows in the Moon.” But REH kept innovating, kept caring about his creation and using Conan and Hyboria as a lens to tell different kinds of stories. It’s extraordinary when you consider the sheer variety represented within the Conan canon, as pure a testament as any to the restless genius of its creator.

Howard: I think that’s a really astute way to look at the tale, or yarn, as Howard himself might have said. He retreated into formula a few times in this series, but he never stayed for too long. Not for him the route of Jules de Grandin and other series creators popular in their day, churning out very similar story to the delight of their readers… very, very few of those writers are still revered today.

Bill: And maybe therein lies a lesson for all artists. If I wanted to just read a Conan story for enjoyment and a sense of adventure, or hook a new reader, “Beyond the Black River” is definitely not what I would choose. But as an enlargement and exploration of one of REH’s primary themes, I don’t think it can be beat. Thank Crom the Conan canon includes both types of stories.

Howard: Well said. Next week we look at “The Black Stranger.” I hope you’ll join us.

20 Comments