Conan Re-Read: The Hour of the Dragon, Part 1

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the first nine chapters of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the first nine chapters of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

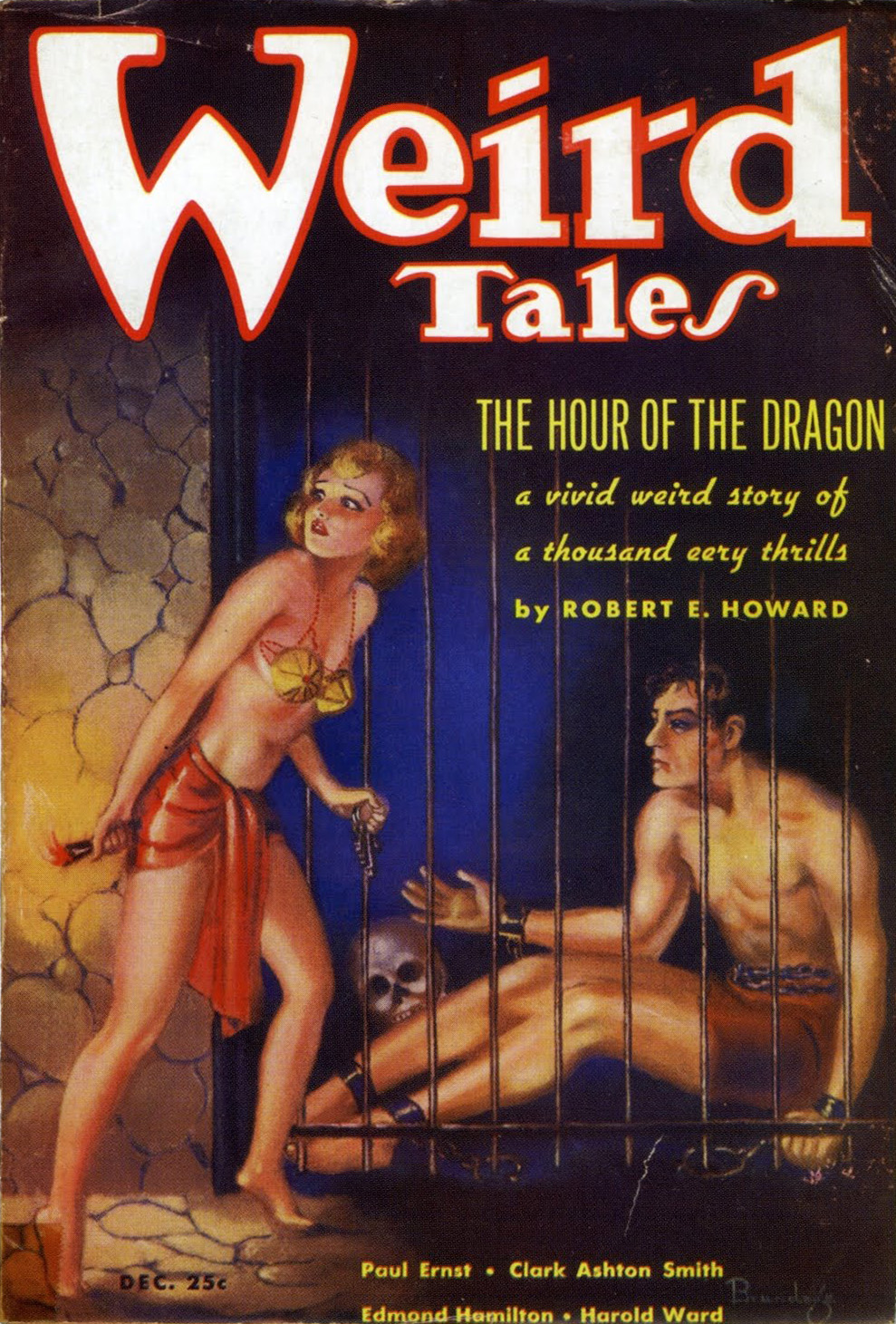

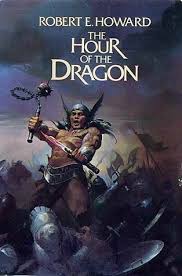

Bill: Last week we looked at the excellent “The People of the Black Circle,” a tale that sees REH growing as a writer and the Conan saga itself expanding in terms of the kinds of stories it can tell. This week we start our discussion of the one and only Conan novel, The Hour of the Dragon, a tale more than twice as long as its predecessor. While, as a commenter pointed out last week, “Black Circle” is described as a novel in its Weird Tales serialized release, The Hour of the Dragon is a true novel in our contemporary sense of the term, both in regards to sheer word count (73,000 words), and in its scale and structure. It is REH’s only completed novel and, as such, to me at least, represents a universe of lost potential from a writer who was clearly capable of mastering the novel form just as he had the short story.

Bill: Last week we looked at the excellent “The People of the Black Circle,” a tale that sees REH growing as a writer and the Conan saga itself expanding in terms of the kinds of stories it can tell. This week we start our discussion of the one and only Conan novel, The Hour of the Dragon, a tale more than twice as long as its predecessor. While, as a commenter pointed out last week, “Black Circle” is described as a novel in its Weird Tales serialized release, The Hour of the Dragon is a true novel in our contemporary sense of the term, both in regards to sheer word count (73,000 words), and in its scale and structure. It is REH’s only completed novel and, as such, to me at least, represents a universe of lost potential from a writer who was clearly capable of mastering the novel form just as he had the short story.

Howard: This is my third time reading the book, and I think I was even more impressed than I was the first. Robert E. Howard was at the top of his game when he wrote it. For decades there was nothing with which to compare this novel on an apple to apple basis because it was so far ahead of what anyone else had done. And then, of course, any direct genre comparison — by which I mean another sword-and-sorcery novel, not merely a fantasy novel — was probably generated after the author read The Hour of the Dragon. The closest we got in any of the decades following was probably Leiber’s The Swords of Lankhmar, which isn’t REALLY a complete novel — it’s more like a fix-up of two novelets, one closely following on the other. And while Swords may be entertaining, it’s not even the best Lankhmar story, let alone in danger of dethroning The Hour of the Dragon.

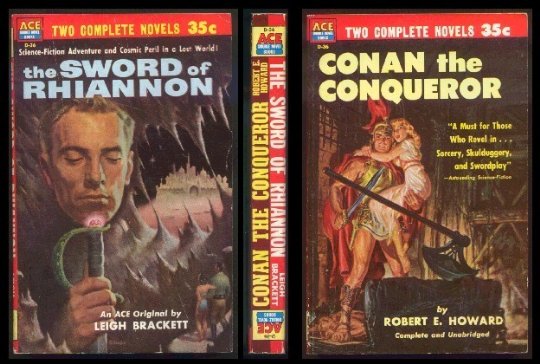

Probably the best ALMOST apples to apples comparison is with Leigh Brackett’s science fantasy/sword-and-planet The Sword of Rhiannon, with which The Hour of the Dragon was presented to the world in a mighty Ace Double book. Talk about a double A side! Still, though, Brackett wasn’t writing an honest-to-goodness sword-and-sorcery novel and she wrote it decades after Howard. No one else was to draft anything like it for years to come.

Probably the best ALMOST apples to apples comparison is with Leigh Brackett’s science fantasy/sword-and-planet The Sword of Rhiannon, with which The Hour of the Dragon was presented to the world in a mighty Ace Double book. Talk about a double A side! Still, though, Brackett wasn’t writing an honest-to-goodness sword-and-sorcery novel and she wrote it decades after Howard. No one else was to draft anything like it for years to come.

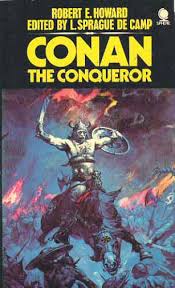

Bill: The novel that would come to be more popularly known as Conan the Conqueror in its Gnome Press and Ace/DeCamp incarnation was the result of a solicitation from a British publisher for a full-length pulp adventure from REH. The same publisher had previously expressed interest in a collection of shorter tales from REH, but had backed out citing lack of market interest in short fiction collections. REH, who had previously expanded the scope of his stories to include nearly every market and genre he had any proclivity to write in, was now about to expand in a different direction by making the leap to long form fiction.

Bill: The novel that would come to be more popularly known as Conan the Conqueror in its Gnome Press and Ace/DeCamp incarnation was the result of a solicitation from a British publisher for a full-length pulp adventure from REH. The same publisher had previously expressed interest in a collection of shorter tales from REH, but had backed out citing lack of market interest in short fiction collections. REH, who had previously expanded the scope of his stories to include nearly every market and genre he had any proclivity to write in, was now about to expand in a different direction by making the leap to long form fiction.

After an abortive stab at the planetary romance novel Almuric, left unfinished by REH and possibly later completed by his agent, Otis Aldebert Kline, REH turned again to the Cimmerian and his Hyborian landscapes. And it is to King Conan, whom we have not seen since “The Scarlet Citadel,” that REH returns to for his epic. Indeed, it’s “The Scarlet Citadel” itself that serves as the rough basis for the plot of The Hour of the Dragon, something that must have been very obvious to readers of the “chronological” Conan saga which published the two stories back-to-back.

Howard: Robert E. Howard scholar Morgan Holmes has a very convincing argument that it was actually Otto Binder (another of Kline’s writer clients) who finished Almuric, owing to certain stylistic similarities between Binder’s prose and the conclusion to Almuric, especially when comparing the “authorial imprint” on those sections to what Kline usually wrote. There may be no way to prove it completely, but Holmes converted me. Unfortunately, my Google-Fu hasn’t been able to turn up the discussion, but if memory serves, Binder was particularly focused upon scent as a sensory input, moreso than Kline or REH ever were (along with some other stylistic fingerprints). When you hold up those final bits next to what Kline or Binder wrote, the authorial voice is as clear as the shagreen pants Jehungir was wearing a couple of weeks back.

Howard: Robert E. Howard scholar Morgan Holmes has a very convincing argument that it was actually Otto Binder (another of Kline’s writer clients) who finished Almuric, owing to certain stylistic similarities between Binder’s prose and the conclusion to Almuric, especially when comparing the “authorial imprint” on those sections to what Kline usually wrote. There may be no way to prove it completely, but Holmes converted me. Unfortunately, my Google-Fu hasn’t been able to turn up the discussion, but if memory serves, Binder was particularly focused upon scent as a sensory input, moreso than Kline or REH ever were (along with some other stylistic fingerprints). When you hold up those final bits next to what Kline or Binder wrote, the authorial voice is as clear as the shagreen pants Jehungir was wearing a couple of weeks back.

Bill: Very interesting, I’ll have to reread Almuric now that I’ve read some Kline, though in no way is that book on the level of the one we are discussing. Roughly the first third of The Hour of the Dragon recalls the plot of “The Scarlet Citadel:” King Conan is betrayed and captured by conspirators aided by a powerful wizard, and his throne usurped by an Aquilonian nobleman. But, while these common elements are present, the novel itself enlarges upon them in every way possible. For instance, the quick set-up of Conan’s betrayal and capture on the battlefield in “Citadel” becomes the far more memorable and exciting chapter in Dragon that sees Conan, about to lead his forces in battle, paralyzed by sorcery and his place on the field taken by another, his army defeated by a magically-provoked landslide, and the king himself captured by a rival ruler and the resurrected wizard Xaltotun. It’s economical, compelling, and gives a great sense of character. It’s the kind of thing you see repeated a few times in this early part of the story — familiar elements are not simply just repeated here, they are re-imagined and reborn anew.

Howard: The opening sequence, when Xaltotun is called back, is immediately evocative and arresting. And there’re so many other excellent moments. There’s even a reason that Conan is kept alive this time, and not simply because the villain is waiting for the proper moment to slay him (i.e. the author needs an excuse to keep him alive). Xaltotun can use Conan as a pawn against the allies he doesn’t trust. And our favorite Cimmerian is in top form, battling on despite infirmities. He may be disturbed by Xaltotun, but he’s not cowed when he meets him.

Howard: The opening sequence, when Xaltotun is called back, is immediately evocative and arresting. And there’re so many other excellent moments. There’s even a reason that Conan is kept alive this time, and not simply because the villain is waiting for the proper moment to slay him (i.e. the author needs an excuse to keep him alive). Xaltotun can use Conan as a pawn against the allies he doesn’t trust. And our favorite Cimmerian is in top form, battling on despite infirmities. He may be disturbed by Xaltotun, but he’s not cowed when he meets him.

Bill: Yes! There is also an even more compelling reason for Aquilonia to think Conan dead, it’s stronger all around. The economy and efficiency of the earliest chapters are perhaps to be expected by a master practitioner of the short story, but one could easily imagine just the opposite emerging from a tight and fast writer attempting his longest work to date — namely verbosity and stretch. And it isn’t just economy of prose and structure, it’s subtle and brilliant choices that keep Dragon as tightly woven as a short story. For instance, REH concludes his opening chapter, which introduces the conspirators, the Heart of Ahriman, and Xaltotun, with a descriptive image of Conan viewed via sorcerous means. In one stroke we are introduced to the protagonist — REH no doubt having to assume that most of his potential audience would be meeting him for the first time — and we are also given a transition directly to the next chapter. But what the description also does is set up the contrast with what’s about to happen — the indomitable warrior-king will at first be rendered helpless, then he’ll be stripped of his kingship. The promise of Conan’s “reverting to type,” a theme that underlies the story, is established twice in lines that show him to be more warrior than aristocrat:

…but the great sword at his side seemed more natural to him than the regal accouterments…His dark, scarred, almost sinister face was that of a fighting-man, and his velvet garments could not conceal the hard, dangerous lines of his limbs.

Reading this, we understand the man in Chapter III who, paralyzed and weakened, makes an impossible stand against his foes, leaning against his tent pole and still summoning the strength to wield his sword. We could have been given this description in Chapter II, say from the point of view of the civilized Pallantides, but instead we get a more intense effect when we see Conan through the eyes of his enemies. Xaltotun, newly resurrected after three thousand years, immediately remarks that this Conan, clearly no Hyborian, is of a people he remembers all too clearly. A people that had never been conquered in his age as well.

Reading this, we understand the man in Chapter III who, paralyzed and weakened, makes an impossible stand against his foes, leaning against his tent pole and still summoning the strength to wield his sword. We could have been given this description in Chapter II, say from the point of view of the civilized Pallantides, but instead we get a more intense effect when we see Conan through the eyes of his enemies. Xaltotun, newly resurrected after three thousand years, immediately remarks that this Conan, clearly no Hyborian, is of a people he remembers all too clearly. A people that had never been conquered in his age as well.

Howard: It’s a fine moment in chapters that are rich with fine moments. You remarked to me how clever it was that the squire relates the battle that Conan can’t see. Much as of Shakespeare’s characters might tell us something that happened (or is happening) off stage, it’s done so skillfully that we’re held spellbound trying to imagine it, especially as we see Conan’s reaction. I’d actually forgotten poor Valannus perished, although you’d think after reading it twice before such a moment would have been indelibly etched in my brain.

Bill: It’s a smart way to not only save space — a full description of the battle could take another chapter — but it also keeps the attention firmly on Conan and builds toward the moment of his capture.

Bill: It’s a smart way to not only save space — a full description of the battle could take another chapter — but it also keeps the attention firmly on Conan and builds toward the moment of his capture.

Thematically, a story of King Conan allows an even greater layer of meaning to creep into the ongoing dialog REH is having about civilization and barbarism. Conan is shown to be a good king because of what kind of man he is, the son of a blacksmith without a drop of royal blood, a man whose moral code was forged in wild and savage lands. When the king, on the run from his captors, pursued by a spying raven, sees an old woman — one of his subjects — being led to a noose by four armored soldiers he does not hesitate to intervene. Indeed, the sight enrages him, for this woman, like all his subjects, is owed his protection as king. Had the woman herself not been a witch with her own ferocious lupine bodyguard, Conan would possibly not have survived the encounter. But the point of course is that Conan understands the reciprocal duties of command, lessons he learned as a pirate, bandit, and raider chieftain. But now that loyalty is not just extended to men who have bled by his side, but to an entire kingdom — Aquilonia and all of its people are his, but not as some mere possession, it and they are his responsibility. Contrast this to the conspirators and, in particular, to the Aquilonain usurper Valerius, and you can see that the self-contained honor of the barbarian (or, at least, this particular barbarian) forges a man of character worthy of the weighty responsibilities of the crown.

Howard: Indeed, and we later see that because Conan values his people, they return their loyalty. He expected nothing of the kind and was doing his duty to a subject when he saves the old woman, but he has “paid it forward,” for we later see how instrumental the witch is in turning the tide against the invaders. She also happens to point Conan toward his next objective. And let me step aside to discuss meta issues here: writers should pay close attention to the through line. At no point do we NOT KNOW why Conan is taking any of his actions. We always know exactly what Conan is doing, where he’s going, and why. There’s almost constant forward momentum, such that when it’s restrained (such as when Conan is held in the dungeon) we feel the same frustration as our protagonist to return to that forward progress.

Howard: Indeed, and we later see that because Conan values his people, they return their loyalty. He expected nothing of the kind and was doing his duty to a subject when he saves the old woman, but he has “paid it forward,” for we later see how instrumental the witch is in turning the tide against the invaders. She also happens to point Conan toward his next objective. And let me step aside to discuss meta issues here: writers should pay close attention to the through line. At no point do we NOT KNOW why Conan is taking any of his actions. We always know exactly what Conan is doing, where he’s going, and why. There’s almost constant forward momentum, such that when it’s restrained (such as when Conan is held in the dungeon) we feel the same frustration as our protagonist to return to that forward progress.

But returning to your point, I think Howard clearly shows us time and again Conan’s capability as both a king and general. His questions about the enemy forces were sharp and insightful, as you’d expect an experienced military leader would be, but then any intelligent tyrant could have noticed these things. Conan, in interacting with his subjects, demonstrates the compulsion toward duty and responsibility of the very best of rulers.

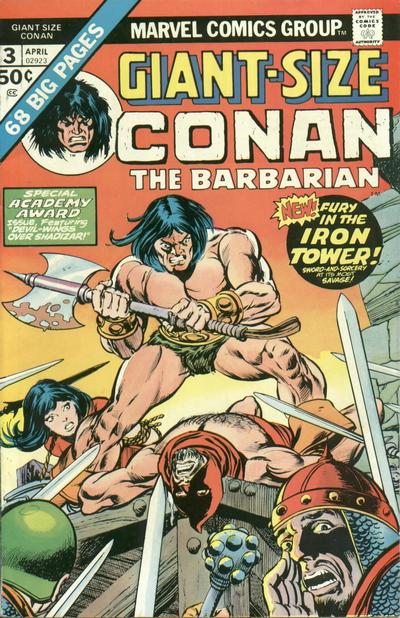

Bill: And, of course, Conan does not flee his endangered Kingdom even when he has the chance, just as a captive Conan refused earlier to cooperate with the men who took his crown away from him. Instead he rushes off to rescue yet another of his subjects, this time the beautiful Countess Albiona, a woman who refuses to be the lover of the usurper and is being held in the Iron Tower of Tarantia, Aquilonia’s capital. Conan demonstrates some of those roguish skills of his early adventuring days by infiltrating both city and tower in disguise. The scene of the rescue, where Conan doffs the executioner’s hood of his disguise and sets about to do an executioner’s work on the men holding the countess hostage, is a satisfying and bloody culmination to the first nine chapters of the novel.

Bill: And, of course, Conan does not flee his endangered Kingdom even when he has the chance, just as a captive Conan refused earlier to cooperate with the men who took his crown away from him. Instead he rushes off to rescue yet another of his subjects, this time the beautiful Countess Albiona, a woman who refuses to be the lover of the usurper and is being held in the Iron Tower of Tarantia, Aquilonia’s capital. Conan demonstrates some of those roguish skills of his early adventuring days by infiltrating both city and tower in disguise. The scene of the rescue, where Conan doffs the executioner’s hood of his disguise and sets about to do an executioner’s work on the men holding the countess hostage, is a satisfying and bloody culmination to the first nine chapters of the novel.

Howard: I loved that entire sequence. It’s immensely satisfying to see Conan triumph at that moment even though he has so many obstacles ahead of him still, and even though all of his foes yet remain alive.

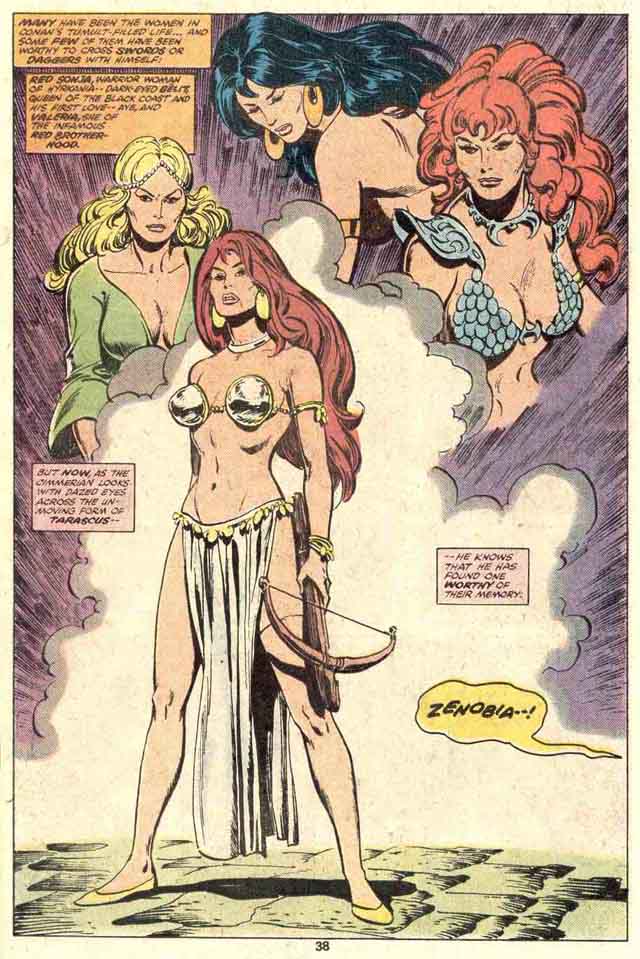

As a final observation for the week, Zenobia is made of awesome. She could have been a weak throwaway character, especially with Howard introducing her as a woman who became enamored of Conan from afar. Left alone after meeting her, Conan shrugs, because beautiful women have risked their lives to aid him before. Yet, isolated as she is, and seeing only lesser men, is it really so strange that she should become fascinated with Conan when she hears about the same escapades that have thrilled all of us? She’s not a star-struck damsel in distress, she’s brave and possessed of “practical intelligence” as we see when she’s managed to sneak a useful dagger to Conan, rather than a pointless stiletto. She went to great pains to engineer an escape, complete with key and horse. Yes, she’s a looker, but it’s her bravery, intelligence, and resourcefulness on the fly that captures Conan’s loyalty, such that he’ll return to claim her as his bride by novel’s end. She has to alter her plans several times once things go awry, and still manages to get him out of Tarascus’ clutches.

As a final observation for the week, Zenobia is made of awesome. She could have been a weak throwaway character, especially with Howard introducing her as a woman who became enamored of Conan from afar. Left alone after meeting her, Conan shrugs, because beautiful women have risked their lives to aid him before. Yet, isolated as she is, and seeing only lesser men, is it really so strange that she should become fascinated with Conan when she hears about the same escapades that have thrilled all of us? She’s not a star-struck damsel in distress, she’s brave and possessed of “practical intelligence” as we see when she’s managed to sneak a useful dagger to Conan, rather than a pointless stiletto. She went to great pains to engineer an escape, complete with key and horse. Yes, she’s a looker, but it’s her bravery, intelligence, and resourcefulness on the fly that captures Conan’s loyalty, such that he’ll return to claim her as his bride by novel’s end. She has to alter her plans several times once things go awry, and still manages to get him out of Tarascus’ clutches.

Bill: She’s great — had she picked a prettier dagger, Conan would have been ape food. And she, as Conan’s future bride, also reminds me of my final point, the obverse of Conan’s barbarian roots supplying his strength as a king, and that’s Conan’s weakness as a dynast. Several times it is mentioned that Conan’s lack of an heir has undermined his position, for there is no one to rally behind after his apparant death. Conan’s conversation with his loyal supporter Servius brings up very realistic points about the usurper’s ability to rule the country, how Conan’s potential army is too dispersed to be of use, and the importance of royal blood. Indeed, Conan realizes that no amount of power of his is equal to Valerius’s nobility and birth in this instance, and I think it’s the final lesson he has to learn to be a true king. His self-contained, wandering spirit must instead lay a solid foundation if he is to serve his people, his sword alone can never be enough to hold a country together.

Bill: She’s great — had she picked a prettier dagger, Conan would have been ape food. And she, as Conan’s future bride, also reminds me of my final point, the obverse of Conan’s barbarian roots supplying his strength as a king, and that’s Conan’s weakness as a dynast. Several times it is mentioned that Conan’s lack of an heir has undermined his position, for there is no one to rally behind after his apparant death. Conan’s conversation with his loyal supporter Servius brings up very realistic points about the usurper’s ability to rule the country, how Conan’s potential army is too dispersed to be of use, and the importance of royal blood. Indeed, Conan realizes that no amount of power of his is equal to Valerius’s nobility and birth in this instance, and I think it’s the final lesson he has to learn to be a true king. His self-contained, wandering spirit must instead lay a solid foundation if he is to serve his people, his sword alone can never be enough to hold a country together.

Howard: Nicely reasoned! Well, we could probably go on for another few thousands words — we just touched on the ape fight — but that leftover turkey’s not going to eat itself. Next week we’ll finish our read through of The Hour of the Dragon, starting with chapter 10. Hope to see you here!

9 Comments