Conan Re-Read: The Hour of the Dragon, Part 2

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the second half of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the second half of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill: It is only at the midpoint of The Hour of the Dragon that Conan learns the full significance of the Heart of Ahriman, the terrible jewel with the intrinsic power to recall the dead to life or enhance sorcery beyond the bounds of mortal power. He learns this from the priests of Asura, a cult that he has shielded from persecution during his reign, and the same priests not only shelter him and the recently rescued princess Albiona, but they also facilitate his journey southward. From this point until its conclusion, the novel is a race for the jewel as Conan travels not only through the Hyborian Age landscape, but through his own past lives as mercenary, pirate, and thief.

Howard: That’s a really good point, Bill. Conan DOES face what he has been, drawing on his experiences and showing us a little how he’s changed. We can wonder whether this was a deliberate ploy of REH to show how Conan functioned in these different environments, slightly changed, or if it was just a simple way to create some action in fields Robert E. Howard was used to working Conan in… but it was probably both, and it works brilliantly.

Bill: The headlong pace of this section of the novel is nothing short of dazzling. Conan pursues, and is himself pursued. He comes close to getting the Heart of Ahriman twice, only to have it snatched away by other hands. He moves from the frontiers of Aquilonia to the Argossean shore, and even to the dark land of Stygia itself — the first time this region, so often mentioned by REH, is featured in a story. From one adventure to the next, from perils supernatural and human, and from one role to another, the pace of the plot is matched only by the pace of the author’s invention.

Howard: And it’s not a frying pan to fire kind of Burroughsian plotting, which, while fun, can grate a little. There’s more to it than that, probably because REH is showing us how Conan has changed, but mostly because Conan’s worried about tracking that jewel and saving his kingdom.

Howard: And it’s not a frying pan to fire kind of Burroughsian plotting, which, while fun, can grate a little. There’s more to it than that, probably because REH is showing us how Conan has changed, but mostly because Conan’s worried about tracking that jewel and saving his kingdom.

Bill: While Conan’s convincing disguise as a mercenary Free Companion is enough to get him into the fortress of Count Valbroso and within inches of grabbing the jewel, it is his old mantle of Amra the Lion that proves more valuable, and integral to the plot. Renewing old contacts with a corrupt and powerful Messantian merchant, Conan, as Amra, barachan pirate and scourge of the sea lanes, is at first betrayed, waylaid, and then pressed into service on the Venturer, a trading galley. This is a familiar situation for anyone who has been reading these tales thus far, and Conan turns the tables on his captors with the aid of the enslaved rowers, many of whom recognize him from his pirating days — and all of whom know him by reputation. It’s a triumphant moment, one that echoes but magnifies similar events in past tales, such as the end of “Iron Shadows in the Moon.” But here such echoes have an even greater weight because they contribute to the ongoing narrative, moving it ever forward.

The climax of Conan’s hunt for the Heart of Ahriman occurs in Stygia, land of ancient evil. Beneath a pyramid of black stone Conan hunts the jewel, though first he escapes the clutches of a beautiful, ageless vampire, Akivasha. Again and again we see Conan tempted in various ways in The Hour of the Dragon, but he refuses all such offers, whether they be to ride off and resume his mercenary wandering, take his newly won ship and turn the seas crimson with his piracy, carve out a new kingdom at the head of the armies of Poitain, or live forever at the side of a creature of flawless beauty. The man who once espoused a live-for-today philosophy in “Queen of the Black Coast” has been tempered by duty, his own honor lending a larger purpose to his existence. Thus, King Conan may slide easily back into the world of his wandering days, but he cannot be, as he once was, truly content in such an existence, not, at least, while his duties remain unresolved.

Howard: That’s a truly important point, especially for those who seem to feel that Conan never changes, or that every adventure is the same. I don’t know how anyone could ever argue that he’s a cardboard figure, for he’s a different man in “The Tower of the Elephant” than he is in “The Phoenix on the Sword,” two stories written very early on showing him at two stages of his life. His perspective on life changes and matures. It’s surely evident here. You’re absolutely right to point out how he’s tempted to slide back into his old ways, or to take an easier, more seductive path, yet he holds true to himself.

Howard: That’s a truly important point, especially for those who seem to feel that Conan never changes, or that every adventure is the same. I don’t know how anyone could ever argue that he’s a cardboard figure, for he’s a different man in “The Tower of the Elephant” than he is in “The Phoenix on the Sword,” two stories written very early on showing him at two stages of his life. His perspective on life changes and matures. It’s surely evident here. You’re absolutely right to point out how he’s tempted to slide back into his old ways, or to take an easier, more seductive path, yet he holds true to himself.

Bill: Khemi, in Stygia, is skillfully evoked in this section of the novel, the oppressive vegetation, the colossal buildings that crush the human spirit. Giant snakes, embodiments of the god Set, feed on the hapless, prostrate citizens of Stygia much as the malignant Thog feasted on the dreamers in “Xuthal of the Dusk.” Conan, of course, is an old hand at killing giant snakes, Stygian or otherwise. His herpecide provokes an angry mob — the willing slaves of Stygia’s priestly caste turning on one who would dare put his life before the dictates of the cult.

Howard: I’d say that this is one of my favorite segments in the book except that the whole book is so strong. Still, the thought of those giant snakes wandering the city and being sacred is pretty grotesque and creepy and inspired. It feels plausible enough that some human society might have thought it a “good” idea… I love how Conan deals with it exactly like we would want to deal with the thing, assuming we had his power and a handy sword.

Bill: The final conflict for possession of the jewel occurs deep underground, in a vaulted tomb overlooked by hundreds of masked dead. The priest Thutothmes seeks to supplant Stygia’s ruler Thoth-Amon, prerequisite to world-conquest, with the aid of an army of the resurrected dead — the irony that Thoth’s previous failure to kill King Conan in “The Phoenix on the Sword” possibly saves his reign from the renegade priest is a fine one. But Conan does not kill Thutothmes, who instead dies at the hands of the Khitan assassins set on Conan’s trail by the usurper Valerius. The Black Hand of Set facing off against the grim wielders of staves cut from the “living Tree of Death” — memorable inventions from REH, who wastes no opportunity throughout the novel to add colorful, fantastic details.

Bill: The final conflict for possession of the jewel occurs deep underground, in a vaulted tomb overlooked by hundreds of masked dead. The priest Thutothmes seeks to supplant Stygia’s ruler Thoth-Amon, prerequisite to world-conquest, with the aid of an army of the resurrected dead — the irony that Thoth’s previous failure to kill King Conan in “The Phoenix on the Sword” possibly saves his reign from the renegade priest is a fine one. But Conan does not kill Thutothmes, who instead dies at the hands of the Khitan assassins set on Conan’s trail by the usurper Valerius. The Black Hand of Set facing off against the grim wielders of staves cut from the “living Tree of Death” — memorable inventions from REH, who wastes no opportunity throughout the novel to add colorful, fantastic details.

Howard: It might be that everything in Stygia is “my favorite bit” from the novel, although they wouldn’t be as strong standing without the rest of the support structure. Here the hero descends into the underworld, facing the dead, and evil wizards, and the alluring vampiress, who is death and sex incarnate, and a powerful symbol of abdication of his true journey. It’s attractive to lose himself in passion and death, to not try to do the hard thing, the right thing, but Conan moves on. And Robert E. Howard paints the events in Stygia, both aboveground and below, so skillfully, that scene piles on scene, splendid and terrifying, at breakneck pace.

Bill: The final, culminating section of The Hour of the Dragon leaves Conan and the jewel on the deck of the Venturer while returning to the conspirators and Xaltotun, moving away from Conan’s point of view through time and space in a choice that once again proves REH’s storytelling instincts. REH could have followed Conan through his return to Aquilonia, his military preparations, his handing over of the jewel to the priests of Asura. Instead, these things happen off stage, and we once again see Conan through the eyes of the conspirators just as we had in the opening sequence of the novel. It’s marvelously effective, elevating Conan’s stature and enhancing his menace, setting the stage for several dramatic revelations, and keeping the forward momentum going without pause.

Howard: He’s incredibly sure-footed, isn’t he? Instead of showing us Conan fretting, wondering what the enemies are doing, we instead see the enemies fretting, and wonder ourselves what Conan might be doing. REH understood that Conan was far more interesting than his villains, and that it would be a lot more fun to be kept in the dark, like the villains. It’s also a way to cut out the boring micromanaging from the narrative. Why follow Conan around as he talks to various allies and lays out his plan? This is much more entertaining.

Bill: The novel has it’s climax in battle, and here, again, REH shines. Battles in the Conan stories have always been well-portrayed, balancing exciting action with plausible strategy and clear narrative. But they have always been somewhat condensed, as the length of a short story dictates — resembling somewhat the Battle of the Valkia at the beginning of the novel, as dictated to Conan by a squire. But the Battle of the Valley of the Lion that caps The Hour of the Dragon is a multi-chapter, multi-scene extravaganza in which the conspirators each meet their doom. Valerius, lead into ambush by those he ruined, Amalric slain on the field by Conan’s lieutenant Pallantides, Xaltotun defeated in the midst of a planned human sacrifice by the witch and the priest of Asura, the latter armed with the Heart of Ahriman itself. A lot happens, but at no point is it disorienting, one section leading naturally to the next with clarity and undeniable momentum.

Howard: Right! Everybody gets their moment in the sun, or, more aptly, their just desserts.

Howard: Right! Everybody gets their moment in the sun, or, more aptly, their just desserts.

Bill: Tarascus, King of Nemedia, the Dragon whose hour has come and gone, is the last of the conspirators to fall, and he meets his fate at the hands of his fellow king. Conan, a man who kills without a moment’s hesitation, spares Tarascus’s life. And here we see Conan emerge fully as a King — while he takes the assault on his kingdom very personally, he does not put his personal interests over those of his people. He needs Tarascus alive to facilitate the withdrawal of Nemedia, and to level indemnities against that kingdom. The hot-headed barbarian who once gutted a man in the maw of Zamora for pushing him, is now the King who thinks three moves ahead. When he asks for Zenobia as ransom from Tarascus, he does so in the same breath as he asks for the other concessions due his kingdom. This is not a woman he intends to treat as a dalliance, this is his future Queen. The wanderer is now truly a King, the Lion will found a dynasty.

Howard: And this got touched upon in the comments last time, but I think it’s abundantly clear that Conan means to wed Zenobia. It’s been demonstrated multiple times at this point that he needs to establish a true line of succession, and a queen will give him an heir. Moreover, as Chris Hocking likes to point out, by God, Conan declares he’s going to marry Zenobia in front of his troops. Conan almost always says exactly what he means. To assume he’d have done something else seems to suggest a fundamental disconnect of a crucial aspect of his personality, or, at least, his maturation.

Howard: And this got touched upon in the comments last time, but I think it’s abundantly clear that Conan means to wed Zenobia. It’s been demonstrated multiple times at this point that he needs to establish a true line of succession, and a queen will give him an heir. Moreover, as Chris Hocking likes to point out, by God, Conan declares he’s going to marry Zenobia in front of his troops. Conan almost always says exactly what he means. To assume he’d have done something else seems to suggest a fundamental disconnect of a crucial aspect of his personality, or, at least, his maturation.

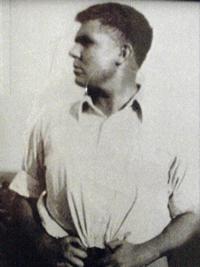

Once again, I think we could have covered this in even more detail. There are any number of lovely passages and grand moments that we’ve only touched on, or overlooked, but this post is on the long side already. I’ll summarize by saying that Bill and I came away from our re-read of this one with an even greater appreciation of Robert E. Howard as a writer. What a grand fantasy novel. We touched on this last week — there was NOTHING remotely like it for decades. Howard was an innovator, something that is overlooked far too often. And, unlike many short story writers turned novelists, his first and only fantasy novel works brilliantly. Would that we lived in a world where he’d gone on to write many more of them.

Next week, join us as we read through another long one, “A Witch Shall be Born.” And don’t forget to join us Monday on Leigh Brackett’s birthday to discuss “The Moon that Vanished.” You can pick up a really affordable copy at BAEN. (Details on the read through and a book link are here.)

5 Comments