Conan Re-Read: “The People of the Black Circle”

Bill Ward and I are starting our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The People of the Black Circle.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are starting our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The People of the Black Circle.” We hope you’ll join in!

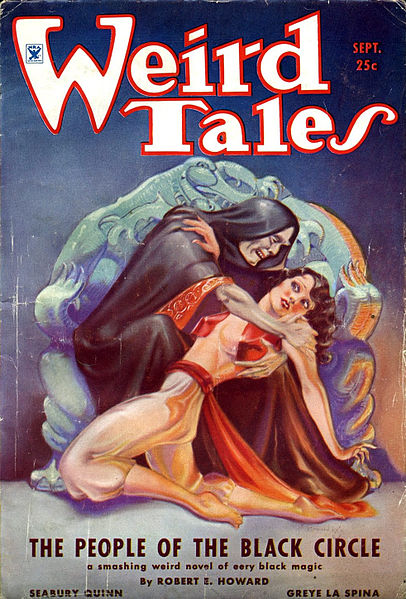

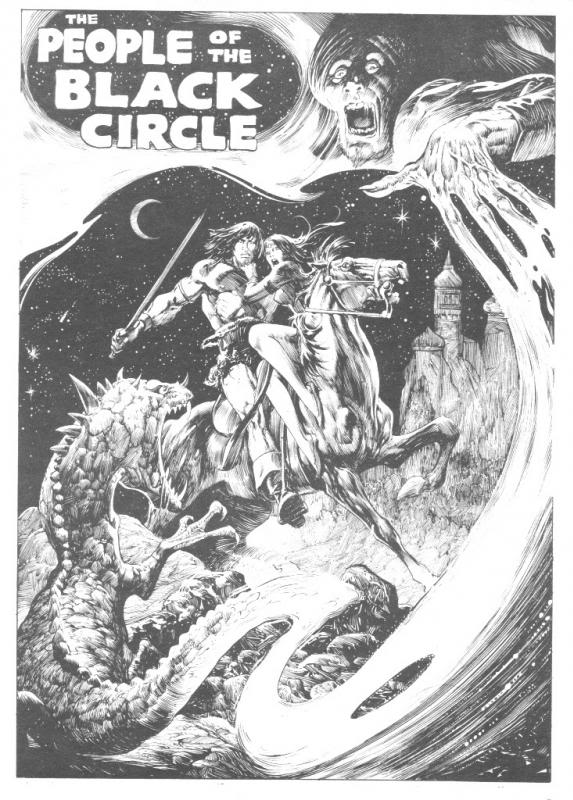

Bill: It’s easy to see why “The People of the Black Circle” is a Conan fan-favorite: plot-twists and action galore, great supporting characters, an exotic but plausibly constructed setting, and fabulous villains using a host of inventive magic. Conan is the adventurer and rogue we’ve come to know over the last dozen or so stories, this time commanding a tribe of Afghuli raiders on the borders of Vedhya, the Hyborian Age equivalent of India. There are a few elements in the story that may recall others in the Conan saga, but this time around there is nothing that feels recycled or borrowed, indeed the whole story feels fresh and something of a departure from what has come before.

Bill: It’s easy to see why “The People of the Black Circle” is a Conan fan-favorite: plot-twists and action galore, great supporting characters, an exotic but plausibly constructed setting, and fabulous villains using a host of inventive magic. Conan is the adventurer and rogue we’ve come to know over the last dozen or so stories, this time commanding a tribe of Afghuli raiders on the borders of Vedhya, the Hyborian Age equivalent of India. There are a few elements in the story that may recall others in the Conan saga, but this time around there is nothing that feels recycled or borrowed, indeed the whole story feels fresh and something of a departure from what has come before.

Howard: It was a grand adventure and a very different feel from the last little parcel of tales. I’m glad REH decided to vary his theme, and I’m scratching my head wondering why this story didn’t serve more often as a sword-and-sorcery template. Probably because its unique character made it far more difficult to imitate.

Bill: “The People of the Black Circle” is a true novella in structure, and at no point does it feel stretched or thinned-out just to pad the length. Patrice Louinet states, in his second installment of the Hyborian Genesis essay in The Bloody Crown of Conan, that much has been made over REH being inspired by Talbot Mundy for this particular story, though no real evidence supports this. To me, this novella feels somewhat like Harold Lamb’s longer works of adventure fiction, a writer REH was clearly influenced by — possibly in a very direct and recent sense, given (our) Howard’s suspicion last week over the word ‘shagreen’ being used in “The Devil In Iron.” Could REH have been re-reading some Lamb and using him for inspiration during this phase of his Conan chronicling?

Bill: “The People of the Black Circle” is a true novella in structure, and at no point does it feel stretched or thinned-out just to pad the length. Patrice Louinet states, in his second installment of the Hyborian Genesis essay in The Bloody Crown of Conan, that much has been made over REH being inspired by Talbot Mundy for this particular story, though no real evidence supports this. To me, this novella feels somewhat like Harold Lamb’s longer works of adventure fiction, a writer REH was clearly influenced by — possibly in a very direct and recent sense, given (our) Howard’s suspicion last week over the word ‘shagreen’ being used in “The Devil In Iron.” Could REH have been re-reading some Lamb and using him for inspiration during this phase of his Conan chronicling?

Howard: At this point REH was enough of his own man that very little of another author’s style is obvious in his fiction. A few of his earlier histories bear an obvious Lamb imprint, but after that, it’s just surface details or atmosphere that he’s pulled from another writer (like “shagreen” last week). The idea that this story is inspired in part by Mundy has to do an awful lot with Mundy’s fiction in Adventure magazine, which dealt with the Khaiber pass, and Afghans, and daring deeds. Mundy and Lamb are generally regarded as the best writers Adventure magazine printed, although naturally there are some who would disagree, and that’s not to say that there weren’t some other quite excellent writers who appeared in its pages. It was chock full of great stories and I bet almost all of our regular readers would have been eagerly reading it every couple of weeks had we been alive back in its day.

REH actually mentioned Mundy in his correspondence more often than he mentioned Lamb. (If you’re curious about Lamb, Mundy, and Adventure, I discuss them in detail here, and of course Lamb in greater detail in all kinds of places, most recently here, which includes some excerpts.)

REH actually mentioned Mundy in his correspondence more often than he mentioned Lamb. (If you’re curious about Lamb, Mundy, and Adventure, I discuss them in detail here, and of course Lamb in greater detail in all kinds of places, most recently here, which includes some excerpts.)

Bill: Great stuff, Howard. Whatever it was that got REH fired-up again to write Conan, he is certainly crafting a story of the highest caliber this time around. In terms of plot “Black Circle” continually shifts itself into higher gear while never once feeling like REH is pulling the strings, something that can’t really be said of some of the more formulaic Conan offerings. Khemsa, one time adept and betrayer of the Black Seers and a more interesting antagonist than we’ve possibly ever had before, sets the plot in motion and manages to undermine Conan several times — but is himself killed only around halfway though the story, some of his strength unexpectedly bestowed upon Conan himself as he squares off against the Black Seers. It’s an unexpected move in a story that is full of them right from the start, when Conan comes barging through a window and spoils the plans being made by more civilized individuals.

Howard: He’s so compelling that I’d completely forgotten he died halfway through. And what a wake-up call to modern writers this pacing should be. I was all prepared for a slow interlude, but apart from a stop here or there to catch our breath, it just keeps moving, twist after twist, shot through with veins of startling imaginative power.

Howard: He’s so compelling that I’d completely forgotten he died halfway through. And what a wake-up call to modern writers this pacing should be. I was all prepared for a slow interlude, but apart from a stop here or there to catch our breath, it just keeps moving, twist after twist, shot through with veins of startling imaginative power.

Bill: The Devi Yasmina is the central civilized character in the story, a beautiful Queen with the strength to kill her own brother to save him from a foul sorcerous assassination. She’s one of the best female “sidekicks” we’ve seen to date, both at once motivated and principled, yet realistically out of her depth in a world of flashing tulwars and sinister magicians. It’s her desire to pit Conan and his raiders against the Black Seers of Yimsha Mountain that puts her in the position to be kidnapped by the Cimmerian, who ultimately accomplishes her purpose only after she herself is captured by the Seers. And the manner in which she and Conan part, as respectful rivals each with their own higher duty and code, is one of the best resolutions in the series, and is part of REH’s ongoing dialog about civilization and kingship.

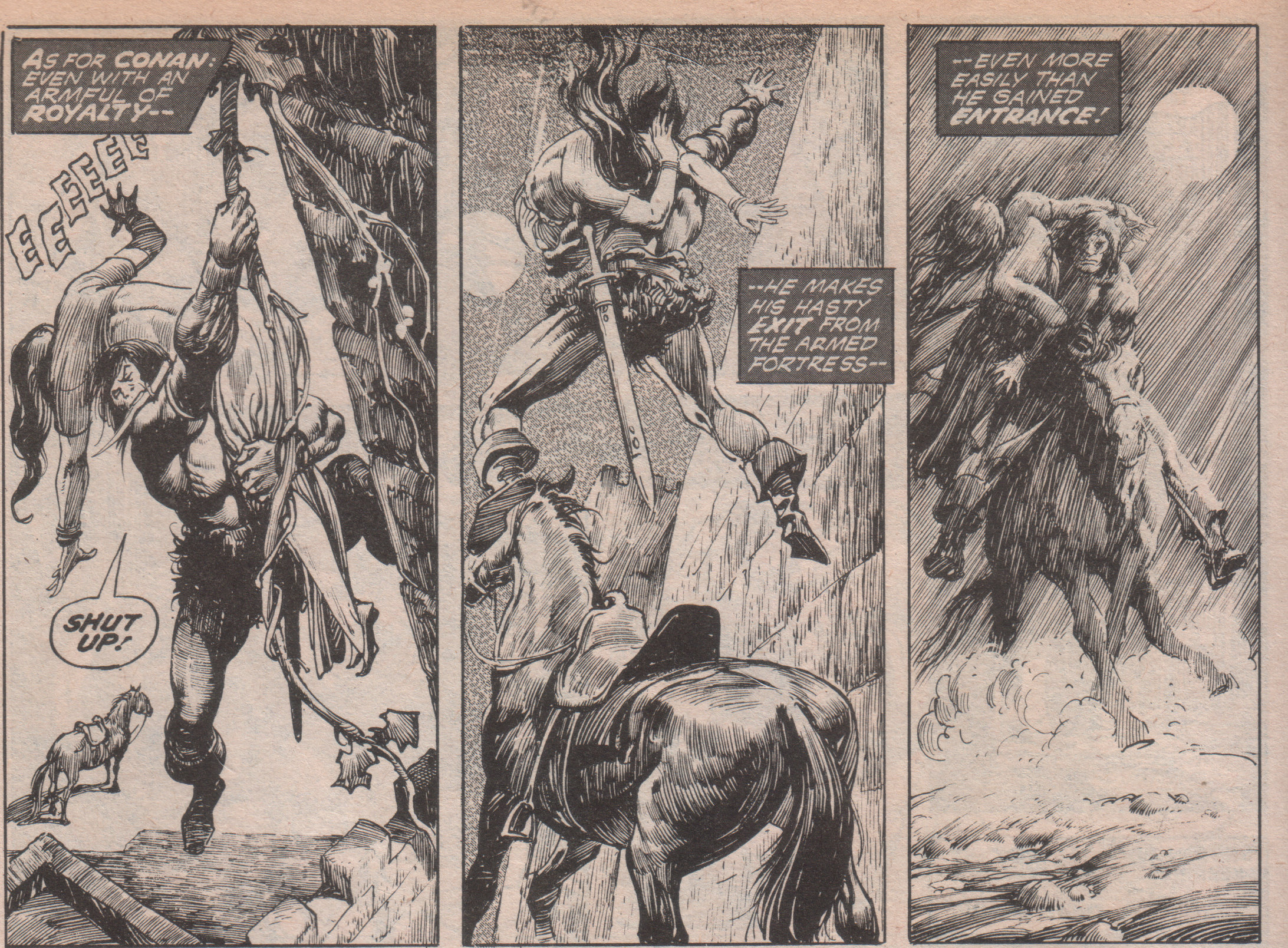

Howard: When REH wants to put the time in to plot, he can plot with the best of them. I think a lot of writers simply would have had him sent on the mission, but I love how Conan shows up, absconds with the Devi, and then ends up on the mission anyway once everything gets twisted out of control. And the shifting alliances were wonderful, probably only exceeded by REH himself, in one of the El Borak stories.

Howard: When REH wants to put the time in to plot, he can plot with the best of them. I think a lot of writers simply would have had him sent on the mission, but I love how Conan shows up, absconds with the Devi, and then ends up on the mission anyway once everything gets twisted out of control. And the shifting alliances were wonderful, probably only exceeded by REH himself, in one of the El Borak stories.

Bill: This story also heavily features a wide variety of creative magic, though remaining perfectly in keeping with the general “low magic” style of REH’s Hyboria. Hypnotism and mind-control are a crucial element, used by Khemsa to good effect several times and, chillingly, during the climax, as members of Kerim Shah’s forces are invited, one by one, to their own decapitation. Conan is immune to the lesser hypnotism deployed by Khemsa (who, with a hypno-stare and a spider-ball, turns an entire tribe against the Cimmerian and Yasmina) because he is not of that culture. That’s a fascinating little gem that goes right back to Conan keeping his sanity in the face of the Elephant God, and also recalls to my mind a terrific scene in Kipling’s Kim, in which the titular character, a westerner highly-assimilated to Indian ways but a westerner nonetheless, is himself immune to illusions brought on by the power of suggestion.

But the adepts of the Black Seers deploy even more wonders in the defense of their tower, possessed wildlife, exploding clouds, even a veritable Horn of Jericho. The chief Black Seer is a shape changer and, in a scene that should make it obvious that the makers of the 1982 Conan film have read this story, changes into a giant serpent to do battle with the Cimmerian. There’s a lot of wild stuff in here, but it never feels outlandish or inappropriate. Much of it fits the setting as well — such as Yasmina being tortured with visions of all her past lives, something we would assume is a fundamental part of Vedhya cosmology.

But the adepts of the Black Seers deploy even more wonders in the defense of their tower, possessed wildlife, exploding clouds, even a veritable Horn of Jericho. The chief Black Seer is a shape changer and, in a scene that should make it obvious that the makers of the 1982 Conan film have read this story, changes into a giant serpent to do battle with the Cimmerian. There’s a lot of wild stuff in here, but it never feels outlandish or inappropriate. Much of it fits the setting as well — such as Yasmina being tortured with visions of all her past lives, something we would assume is a fundamental part of Vedhya cosmology.

Howard: I loved it. I can’t believe I haven’t re-read this one more often. The magic was so inventive, and so NOT standard role-playing magic. I think too many of us now have grown up playing those games where spells behave a certain way. There’s no telling what’s going to happen with magic in one of these tales because it’s beyond our ken. It’s subtle and horrific. Never flashy, but usually fear inducing. I think it’s masterful that we don’t even SEE the horror that Khemsa calls up!

Bill: Of course, Conan has his own way of dealing with all this magic, giving the great line “a good knife is always a hearty incantation.” He moves through the region of Afghulistan a barbarian among barbarians, and REH does a terrific job integrating the Cimmerian into this world, showing both some of the personal ties he has developed, and the two-edged sword of his own status. It’s all a very evocative and unsentimental look at what these societies were (and are) like, where the rule of a strong hand can be upset by the merest rumor or suspicion, especially of a foreigner. That Conan can not only survive, but prosper, in such an environment is perhaps even more impressive than his ability to shrug off a Mesmer stare or skewer a swooping wizard-hawk. We get a sense of just why that might be at the very end when, witnessing his raiders getting slaughtered, Conan rushes to their aid — and this after they had already called for his blood as a traitor. Conan is always loyal to his companions, and I think it’s that trait that is the core of what makes him a great leader and, eventually, a great king.

Bill: Of course, Conan has his own way of dealing with all this magic, giving the great line “a good knife is always a hearty incantation.” He moves through the region of Afghulistan a barbarian among barbarians, and REH does a terrific job integrating the Cimmerian into this world, showing both some of the personal ties he has developed, and the two-edged sword of his own status. It’s all a very evocative and unsentimental look at what these societies were (and are) like, where the rule of a strong hand can be upset by the merest rumor or suspicion, especially of a foreigner. That Conan can not only survive, but prosper, in such an environment is perhaps even more impressive than his ability to shrug off a Mesmer stare or skewer a swooping wizard-hawk. We get a sense of just why that might be at the very end when, witnessing his raiders getting slaughtered, Conan rushes to their aid — and this after they had already called for his blood as a traitor. Conan is always loyal to his companions, and I think it’s that trait that is the core of what makes him a great leader and, eventually, a great king.

Howard: Indeed, and the concluding notes of this one intimate that destiny further. I love that he and Yasmina part as equals. She’s a woman to be admired, and he sees it. Not for this story the fade-out with the beautiful damsel, but a little bittersweet taste of a love that can’t be realized. They part in respect.

Howard: Indeed, and the concluding notes of this one intimate that destiny further. I love that he and Yasmina part as equals. She’s a woman to be admired, and he sees it. Not for this story the fade-out with the beautiful damsel, but a little bittersweet taste of a love that can’t be realized. They part in respect.

I did notice one thing — there weren’t any passages in this one that were so stunning that I stopped in my tracks to re-read them. This isn’t meant as a knock in any way, and it might be simply that I was so caught up in the narrative that I didn’t notice. But I was reminded of that great passage in “Phoenix on the Sword” when Thoth-Amon lays hold of his ring, and the bit from “Iron Shadows in the Moon” when Olivia drowses while Conan rows. There’s nothing of that power in this narrative. Yet this is a far stronger story and completely satisfying. Maybe it just didn’t need anything like hat.

Next week, we’ll take a look at the first half of The Hour of the Dragon, the only Conan novel drafted by Robert E. Howard. I think we can read the first nine chapters by then. Heck, I think the hardest thing will be stopping at nine. It’s even better than I remembered!

13 Comments