Heroes of the Steppes: The Historicals of Harold Lamb

This article I wrote some years back has been floating around on the inter web in a couple of places, and I thought it past time for me to bring it back to my own site. So — here you go!

This article I wrote some years back has been floating around on the inter web in a couple of places, and I thought it past time for me to bring it back to my own site. So — here you go!

Before Stormbringer keened in Elric’s hand, before the Gray Mouser prowled Lankhmar’s foggy streets—before even Conan trod jeweled thrones under his sandaled feet, Khlit the Cossack rode the steppe. He isn’t the earliest serial adventure character, but his adventures are among the earliest that can still be read for sheer pleasure.

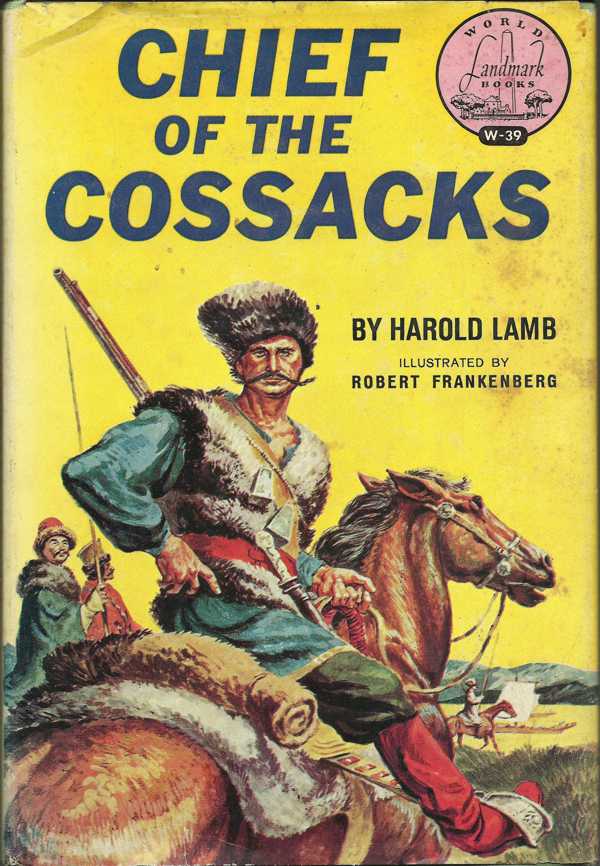

He was created in 1917 by Harold Lamb, in a time when “costume pieces” provided the same kinds of thrills that fantasy and science fiction adventure stories deliver today, and he appeared in the pulp magazines.

The best remembered of these magazines today are probably those devoted to the adventures of single characters—like Doc Savage or The Shadow—or the early magazines of the fantastic wherein those we now recognize as giants were published—Weird Tales, and, later, Unknown, Planet Stories, and other science fiction magazines.

Shortly after World War I, though, there was very little to be found in the realm of the fantastic. For all their fame, the later science fiction magazines and Weird Tales were hardly representative of the content found in most pulps. The most popular of magazines tended to be devoted to westerns and detective tales. Aside from the occasional Verne reprint and a few innovators—like the fellow who’d written of a civil war soldier transported to Mars—adventure was found in more recognizable places.

And then came Lamb.

About forty loosely linked novelettes in Adventure narrated the adventures of several Cossack heroes in the early seventeenth century… They are tales of wild adventure, full of swordplay, plots, treachery, startling surprises, mayhem, and massacre, laid in the most exotic setting that one can imagine and still stay in a known historical period on this planet.[1]

About forty loosely linked novelettes in Adventure narrated the adventures of several Cossack heroes in the early seventeenth century… They are tales of wild adventure, full of swordplay, plots, treachery, startling surprises, mayhem, and massacre, laid in the most exotic setting that one can imagine and still stay in a known historical period on this planet.[1]

Lamb’s fiction exploded with cinematic pacing. Expect slow spots when you’re reading even the best historicals from Lamb’s time, but don’t look for them in his work. It drove forward at breakneck pace, paused briefly to gather a breath, then plunged the reader back into suspense. It rang with the shouts of battle and the clang of swords. It swam in an atmosphere as heady and exotic to western eyes as Burroughs’ Mars. Consider this passage, composed in 1921. Khlit the Cossack is leading a small army of Tartars into battle against an army of the Mogul’s, many of whom ride massive war elephants, raining death from the howdahs perched upon the backs of the mighty beasts:

Khlit pointed to the howdah of the Northern Lord, glittering with its costly trimmings.

“Chagan, take a score of followers and slay me that chief.”

By now the arrows from the howdahs were flying among the Tatar riders, and their own arrows were deflected off the armored coverings of the beasts. Khlit rose to a standing position in his saddle and surveyed the masses of fighting men. He rode swiftly from clan to clan, bidding them draw away from the riverbank. In so doing they passed near the elephant of Paluwan Khan.

By now the arrows from the howdahs were flying among the Tatar riders, and their own arrows were deflected off the armored coverings of the beasts. Khlit rose to a standing position in his saddle and surveyed the masses of fighting men. He rode swiftly from clan to clan, bidding them draw away from the riverbank. In so doing they passed near the elephant of Paluwan Khan.

Chagan had driven his horse at the head of the giant beast, clearing a path for himself with his sword. He swung at the black trunk that swayed above him, missed his stroke, and went down as his horse fell with an arrow in its throat.

“Bid your elephant kneel, cowardly lord,” he bellowed, springing to his feet and avoiding the impact of the great tusks, “and fight as a man should!”

His companions being for the most part slain, Chagan seized a fresh mount that went by riderless and rode against the elephant’s side. Gripping the canopy that overhung the elephant’s back, with teeth and clutching fingers he drew himself up, heedless of blows delivered upon his steel headpiece and mailed chest.

“Ho!” he cried from between set teeth. “I will come to you, Northern Lord!”

“Ho!” he cried from between set teeth. “I will come to you, Northern Lord!”

An arrow seared his cheek and a knife in the hand of an archer bit into the muscles of a massive arm. Chagan’s free hand seized the mahout and jerked him from behind the ears of the elephant as ripe fruit is plucked from a tree. At this the beast swayed and shivered, and for an instant the occupants of the howdah were flung back upon themselves and Chagan was nearly cast to earth.

Kneeling, holding on the howdah edge with a bleeding hand, he smote twice with his heavy sword, smashing the skull of an archer and knocking another to the ground. The remaining native thrust his shield before Paluwan Khan.

But the Northern Lord, no coward, pushed his servant aside and sprang at Chagan, scimitar in hand.

The Tatar sword-bearer, kneeling, wounded, was at a disadvantage. Swiftly he let fall his own weapon and closed with Paluwan Khan, taking the latter’s stroke upon his shoulder. A clutching hand gripped the throat of the Northern Lord above the mail and Chagan roared in triumph.

Pulling his foe free of the howdah, the Tatar lifted Paluwan Khan to his shoulder and leaped from the back of the elephant.

Pulling his foe free of the howdah, the Tatar lifted Paluwan Khan to his shoulder and leaped from the back of the elephant.

The two mailed bodies struck the earth heavily, Paluwan Khan underneath; and it was a long moment before Chagan rose, reeling. In his bleeding hand he clasped the head of the Northern Lord. And, reeling, he made his way to Khlit, through the watchers who had halted to view the struggle upon the elephant.

“Kha Khan, look upon your foe!”

And Chagan tossed the head aside, to run, staggering, at Khlit’s stirrup as the Tatars swept athwart the Mogul’s line, away from the river.[2]

Prior to creating Khlit, Lamb had worked steadily in the pulps for a number of years, cracking the prestigious Argosy and a number of other magazines. His early stories are sometimes entertaining but rarely remarkable. Anyone familiar only with these pieces, set at the time of their composition, probably wonders what all the fuss is about.

The fuss began shortly after Lamb broke into Adventure, later christened the “dean of pulp magazines” by Newsweek. It was, as Bob Weinberg has written, “the very best the pulps had to offer.”[3]

The fuss began shortly after Lamb broke into Adventure, later christened the “dean of pulp magazines” by Newsweek. It was, as Bob Weinberg has written, “the very best the pulps had to offer.”[3]

Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, Adventure’s editor, gave Lamb leave to write about what he liked best, and what Lamb liked best were stories set in the East. He had discovered histories of Asia while in the libraries of Columbia, prior to the war, and described them as “gorgeous and new.” Born with what he later described as damaged eyes, ears and speech—though he wrote that those defects had mostly righted themselves by the time he was an adult–Lamb alternated his time growing up between his grandfather’s library and the outdoors. Hoffman described him as a compulsive scholar, but Lamb seemed to prefer studying those subjects which interested him rather than those required for school, for he nearly flunked out of Columbia, where he was to be found on the tennis court when he was not in the book stacks.

Lamb’s writing hit its stride when he drafted a tale set in a Cossack camp in the 16thcentury. “Khlit” is short and relatively slight compared to what came after, but there is potential in the work; reading it is like glimpsing the embers in a fireplace as they begin to glow red. No longer writing of the West and familiar settings, Lamb shed conventions and stereotypes and dove headlong into storytelling. He wrote a longer sequel to “Khlit” and the potential glimpsed in the first story brightened into flame. This tale was followed by another, at which point Lamb’s creation blazed like a roaring bonfire.

Lamb had found a setting that allowed him to write to his strengths and minimize his weaknesses. He had immersed himself in the times and places and brought them vividly to life, though he never bogged the reader down with detail. David Drake touches on this in an introduction to Volume 2 of Lamb’s Cossack stories, Warriors of the Steppes: “The author keeps the real historical background a shadowy presence enveloping his stories instead of trotting it out to prove his erudition; but the more a reader knows of that background, the more certain he becomes that Lamb had all the details at his fingertips.”

Lamb had found a setting that allowed him to write to his strengths and minimize his weaknesses. He had immersed himself in the times and places and brought them vividly to life, though he never bogged the reader down with detail. David Drake touches on this in an introduction to Volume 2 of Lamb’s Cossack stories, Warriors of the Steppes: “The author keeps the real historical background a shadowy presence enveloping his stories instead of trotting it out to prove his erudition; but the more a reader knows of that background, the more certain he becomes that Lamb had all the details at his fingertips.”

Lamb placed his emphasis on conveying the story rather than conveying his scholarship, and he made each tale unique. In adventure fiction we are used to and often make excuses for the fact that certain elements appear and re-appear time and again. We may even see the same plot redressed by the same author–as Edgar Rice Burroughs so often did with his tales of Tarzan or John Carter–or have a good sense of how it will all turn out after the first few pages. Not so with Lamb. Even a jaded reader, even one familiar with Lamb’s work, is unlikely to anticipate the turns his plots will take. His characters do not remain static–they change, they age, and some of them die.

The Cossack frontier and the steppe were an inspired choice for an adventure series, and the 16th century the perfect period for it. Empires were dying and a-borning, and in that chaos a single man could make his own destiny, carving it out of the wreck with a saber. Christian and Muslim, Buddhist and shamanist, hunter and herder and farmer and city-man met and connived and struggled over half a world.[4]

Harold Lamb sent Khlit adventuring into the dangerous, shifting border between Russia and lands to the east and south. His hero was a Cossack, one of that breed who lived in picked war camps along the frontier–self appointed protectors who had all the independence and skilled horsemanship of an American cowboy, the camaraderie of The Three Musketeers, and a reputation a little like a cross between the famed French Foreign Legion and pirates. Tricksters, daredevils, vagabonds, the Cossacks lived a dangerous and exciting existence. “For weapons, the free Cossacks were forced to rely on what they could take from the Moslems, who were the best armed troops in Europe at that time. No one received any pay… Only two conditions were made to a newcomer; he must be able to use weapons, ride and take care of himself, and he must be a believer in God and Christ. Every new arrival was expected to perform some feat to show his worth. A good many died in attempting to shoot the cataracts of the Dneiper, or in jumping their horses over the palisade around the camp.”[5]

Harold Lamb sent Khlit adventuring into the dangerous, shifting border between Russia and lands to the east and south. His hero was a Cossack, one of that breed who lived in picked war camps along the frontier–self appointed protectors who had all the independence and skilled horsemanship of an American cowboy, the camaraderie of The Three Musketeers, and a reputation a little like a cross between the famed French Foreign Legion and pirates. Tricksters, daredevils, vagabonds, the Cossacks lived a dangerous and exciting existence. “For weapons, the free Cossacks were forced to rely on what they could take from the Moslems, who were the best armed troops in Europe at that time. No one received any pay… Only two conditions were made to a newcomer; he must be able to use weapons, ride and take care of himself, and he must be a believer in God and Christ. Every new arrival was expected to perform some feat to show his worth. A good many died in attempting to shoot the cataracts of the Dneiper, or in jumping their horses over the palisade around the camp.”[5]

Khlit, also known as the Wolf, is owner of a curious sword which has earned him the additional sobriquet of Khlit of the curved saber. Contrary to current trends in popular fiction, where the hero is a stripling coming into his own (a la Luke Skywalker, Frodo Baggins, or uncounted numbers of stable boys destined to be kings), or a grown man seasoned with experience but still in the prime of life (Indiana Jones, James Bond), Khlit is an older man from his first adventure. He is one of a very few Cossacks who has survived into his middle-years. This is no accident, and while we soon see that Khlit is a fine horseman and sword wielder, it is his keen intellect which sees him through so many escapades. Archetypally he is not Achilles, Luke Skywalker, or Superman–he is modeled from wily Odysseus.

Lamb didn’t leave Khlit in the Cossack camp for long. When enemies try to force Khlit into “retirement” (meaning into a monastery) at the opening of the third tale, Khlit will have none of it, and gallops off into the wilds of Asia, China, and India. It’s a glorious ride. With him we infiltrate the hidden fortress of assassins, Alamut, track down the tomb of Genghis Khan, flee the vengeance of a dead emperor, lead the Mongol horde against impossible odds, safeguard a stunning Mogul queen through the lands of her enemies, stamp out a cult of stranglers, and much more. His nineteen tales, some of them short novels, are adventure writing at its very finest, awash with ancient tombs, gleaming treasure, and thrilling landscapes. Khlit matches wits with deadly swordsmen, scheming priests, and evil cults; he rescues lovely damsels, rides with bold comrades, and hazards everything on his brains, skill, and luck.

Lamb didn’t leave Khlit in the Cossack camp for long. When enemies try to force Khlit into “retirement” (meaning into a monastery) at the opening of the third tale, Khlit will have none of it, and gallops off into the wilds of Asia, China, and India. It’s a glorious ride. With him we infiltrate the hidden fortress of assassins, Alamut, track down the tomb of Genghis Khan, flee the vengeance of a dead emperor, lead the Mongol horde against impossible odds, safeguard a stunning Mogul queen through the lands of her enemies, stamp out a cult of stranglers, and much more. His nineteen tales, some of them short novels, are adventure writing at its very finest, awash with ancient tombs, gleaming treasure, and thrilling landscapes. Khlit matches wits with deadly swordsmen, scheming priests, and evil cults; he rescues lovely damsels, rides with bold comrades, and hazards everything on his brains, skill, and luck.

Gruff and taciturn, Khlit is a firm believer in justice. He is the friend and protector of many women, but he leaves romance to his sidekicks and allies. He rides alongside heroes from many different nationalities, with varied beliefs-—among them a heroic Afghan swordsman, a Manchu Archer, a Hindu warrior, and daring Mongol horsemen. And not all of his allies are men:

Weakly Chepé Buga staggered out into the hall. His companion closed the door behind him. Then the khan sank down beside Atagon. For the first time he saw his companion by the firelight. Even to his dimmed eyes the figure did not seem like Chagan’s bulk. The firelight gleamed on the small shield of Atagon which the other carried.

Weakly Chepé Buga staggered out into the hall. His companion closed the door behind him. Then the khan sank down beside Atagon. For the first time he saw his companion by the firelight. Even to his dimmed eyes the figure did not seem like Chagan’s bulk. The firelight gleamed on the small shield of Atagon which the other carried.

Above the shield was a white, anxious face and a tangle of gold hair.

“Chinsi!” he gasped. “How–”

“Chagan could not leave the tower,” she said softly, “they are hard beset. I took Atagon’s sword and shield, to help you if I could.” The girl laid down her shield and knelt beside him.

“They have gone from the door,” she said eagerly, “I heard them.”

Her glance fell on the dark stain that covered the khan’s mail, and she gave a cry of dismay.

Chepé Buga shook his head in mute protest as she tried to draw off his heavy mail.

“The spear,” he whispered, “went deep. Your sword killed the man that did it. Brave Chinsi, the golden-haired!“

Chepé Buga’s dark head sank back on the floor, and his sword fell from his fingers. The watching girl saw a gray hue steal into his stern face. Chepé Buga, she knew, was dying.

Chepé Buga’s dark head sank back on the floor, and his sword fell from his fingers. The watching girl saw a gray hue steal into his stern face. Chepé Buga, she knew, was dying.

“Harken,“ she whispered, pointing to Atagon who lay beside them, conscious. “Let the presbyter bless you, Chepé Buga. The priest will save your soul, for heaven.”

The Tatar moved his head weakly until he could see Atagon. Something like a smile touched his drawn lips. The girl bent her head close to his to hear what he was trying to say.

“Nay, Chinsi. Do you bless me. Heaven is—-where you are.”

Raising one hand, Chepé Buga caught a strand of the girl‘s hair which lay across his face. The girl, who had stretched out her hand to Atagon, sighed regretfully. Yet she did not move her head away.

Chepé Buga’s hand was still fast in her hair. But its weight hung upon the strand, and the Tatar’s eyes were closed when Khlit and Chagan ran from the tower stairs into the hall a moment later.[6]

Over the course of his journeys Khlit may bear some of his own prejudices with him, but his perceptions grow and change: the Cossack first views Tatars as hereditary enemies, then embraces their culture as his own. And then there is the devoted friendship shared between Khlit and Abdul Dost, who teams up with the Cossack in four stories of the saga; an Eastern Orthodox Christian and a Muslim. Both are devout in faiths that have lost little love for one another, yet the men are brothers of the sword. Lamb has no theological or philosophical axe to grind–he aims only to present a cracking good story, and he almost always succeeds.

Over the course of his journeys Khlit may bear some of his own prejudices with him, but his perceptions grow and change: the Cossack first views Tatars as hereditary enemies, then embraces their culture as his own. And then there is the devoted friendship shared between Khlit and Abdul Dost, who teams up with the Cossack in four stories of the saga; an Eastern Orthodox Christian and a Muslim. Both are devout in faiths that have lost little love for one another, yet the men are brothers of the sword. Lamb has no theological or philosophical axe to grind–he aims only to present a cracking good story, and he almost always succeeds.

Lamb never wrote overtly of the fantastic or the supernatural like Robert E. Howard, keeping his historical fiction grounded in reality, but he did play around its edges, frequently exposing his characters to the strange and macabre. Some of his villains masquerade as sorcerors and miracle workers of great power. Here Khlit and his Tatar friend Chagan follow a ghostly noise arising from ruins near a desert mound in “Roof of the World:

The hair had not descended to its normal position on the back of Chagan’s head when Khlit joined him. The Cossack had heard the voice. The two men gazed at the mound curiously.

“Said I not the place was rife with evil spirits?” growled the sword-bearer. “That is the song I heard in the night.”

“Said I not the place was rife with evil spirits?” growled the sword-bearer. “That is the song I heard in the night.”

The voice dwindled and was silent. Khlit inspected the stone ruins which showed through the sand. Then he motioned to Chagan.

“Here is no sand dune,” he growled. “The sand has covered up a building, and one of size. Some parts of the walls show through the sand. If we look we will find a woman in the ruins.”

“Nay, then she must eat rock and drink from the Jallat Kum[7],” protested the Tatar. “If there was a house here, even a palace, the sand has filled it up–”

Nevertheless he followed Khlit as the Cossack climbed over the debris of rock that littered the sides of the mound. They went as far as they could, stopping at the edge of the basin which the mound adjoined. There was no sign of a person among the remnants of walls. But Khlit pointed to the tower on the summit of the mound.

Chagan objected that there were no footsteps to be seen leading to the ruined tower. Khlit, however, solved this difficulty by scrambling up the slope. The shifting sand, dislodged by his progress, fell into place again behind him, erasing all mark of his footsteps. He vanished into the pile of masonry. Presently he reappeared and directed Chagan to bind together a torch of dead tamarisk branches and to light it at their fire.

When the sword-bearer had done this, Khlit assisted him to the summit of the hillock. There he pointed to the stone tower. Its walls had crumbled into piles of stones, projecting from the sand no more than the height of a man, but in the center of the walls a black opening led downward.[8]

When the sword-bearer had done this, Khlit assisted him to the summit of the hillock. There he pointed to the stone tower. Its walls had crumbled into piles of stones, projecting from the sand no more than the height of a man, but in the center of the walls a black opening led downward.[8]

A private man, details about Lamb’s home life are scarce. He married Ruth Barbour in 1917, and by all accounts their marriage was a long and happy one. They had two children, Frederick and Cary. He served in both world wars–as an infantry man in World War I (though he saw no action) and as an O.S.S. operative overseas in World War II. Lamb knew many languages: by his own account, French, Latin, ancient Persian, some Arabic, a smattering of Turkish, and a bit of Manchu-Tartar and medieval Ukranian. He traveled throughout Asia, visiting most of the places he wrote about.

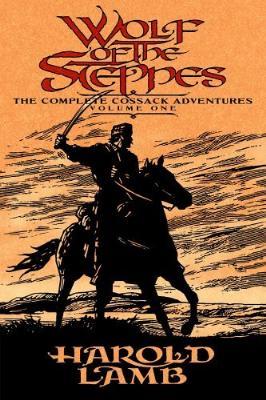

As the pulp magazine market dried up, Lamb moved on to write well regarded histories and biographies, and co-wrote numerous screenplays for Cecil B. Demille. Because of his expertise in the Middle-East, he was sometimes consulted by the state department. His pulp work was mostly forgotten until the very end of his life, when Lamb was asked to select a handful of Cossack stories for reprint by Doubleday. He did not live to see the collection printed, and most of his adventure stories have languished in obscurity until 2006, when they were collected in trade paperback by the University of Nebraska Press’s Bison Books imprint.

The volumes feature appendices with never-before-reprinted letters from Lamb about his stories, introductions from fantasy and science fiction luminaries like David Drake, S.M. Stirling, and E.E. Knight, and a gorgeous interior map detailing Khlit’s travels.

The Cossack stories have never been available in a complete set, in order, and some have never seen print since their Adventure days. It is my sincere hope that they will now, at last, be discovered and celebrated and enjoyed by legions of heroic fiction fans familiar with authors and works that might never have existed without Lamb to lead the way.

[1] de Camp, L. Sprague. Marching Sands. “Harold Lamb.” New York: Hyperion, 1974.

[2] Lamb, Harold. “The Curved Sword.” Adventure. November 1, 1920.

[3] In his introduction to Swords from the West.

[4] Stirling, S.M. “Introduction.” Wolf of the Steppes. Bison Books, 2006.

[5] Lamb, Harold. Letter to Adventure, published in 10/20/1923 “The Camp-Fire” letter column.

[6] Lamb, Harold. “Changa Nor.” Adventure. Feb. 1, 1919.

[7] Quicksand.

[8] Lamb, Harold. “Roof of the World.” Adventure. April 15, 1919.

7 Comments