Robert E. Howard’s Birthday

Here’s to Robert E. Howard, creator of my favorite genre, sword-and-sorcery, on the anniversary of his birth. Raise high your goblets and drink deep.

Here’s to Robert E. Howard, creator of my favorite genre, sword-and-sorcery, on the anniversary of his birth. Raise high your goblets and drink deep.

What is best about Robert E. Howard’s writing? The driving headlong pace, the seemingly inexhaustible imagination, the splendid cinematic prose poetry, the never-say-die protagonists? It is hard to pick one thing, so it may be simpler to state that Robert E. Howard possessed profound and often astonishing storytelling gifts. Without drowning his readers in adjectives (he had the knack of using just enough adjectives or adverbs, and knew to let the verbs do the heavy lifting) or slowing pace, he brought his scenes to life. Vividly.

Writer Eric Knight may have most succinctly described this particular aspect of Howard’s power in an article on Solomon Kane:

“’Wings of the Night’ features a marathon running fight through ruin, countryside, and even air that only a team of computer animators with a sixty-million dollar budget and the latest rendering technology (or a single Texan from Cross Plains hammering the story out with worn typewriter ribbon) could bring properly to life.”

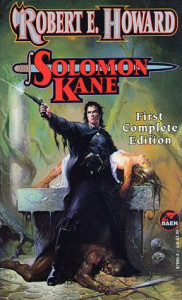

Howard was only 30 when he died in 1936, meaning the bulk of his best prose — and there was a lot of it — was created when he was between 25 and 30 years of age, which makes his achievements that much more astonishing. Bram Stoker, Ian Fleming, and Arthur Conan Doyle created characters who are now rooted firmly in our popular imagination. Edgar Rice Burroughs did the same with Tarzan, and anyone who digs even a little further into his work knows John Carter is an also ran. Howard’s Conan, too, has achieved popular recognition, but there is much more to Howard than the dull barbarian depicted in the movies, one which bears but passing resemblance to the character from the stories. There was King Kull, and Solomon Kane, and Bran Mak Morn, and El Borak, and more obscure characters like James Allison, Steve Costigan, and one of my personal favorites, Turlogh Dubh O’Brien. The deeper you dig into Howard’s canon, the more treasures you find. Some of my most favorite stories are his historicals, never as popular among readers perhaps because there are so few serial characters among them, or perhaps because there are few fantastic elements within. The action and pace and all else is there, along with some of his very finest prose and plotting.

I didn’t really discover Howard until nearly 20 years ago, when I decided that if I was serious about writing fantasy I needed to explore its roots and understand where it came from. Oh, I’d seen Conan on the bookshelves and on comic book covers, but the endless rows of pastiche Conan and the fellow who was frequently running around in a loincloth on those covers didn’t much interest me. I incorrectly assumed it was all rubbish.

I didn’t really discover Howard until nearly 20 years ago, when I decided that if I was serious about writing fantasy I needed to explore its roots and understand where it came from. Oh, I’d seen Conan on the bookshelves and on comic book covers, but the endless rows of pastiche Conan and the fellow who was frequently running around in a loincloth on those covers didn’t much interest me. I incorrectly assumed it was all rubbish.

Most of the pastiche IS rubbish, although I have a few favorites among that work, but more to the point, when I finally read the actual Robert E. Howard prose and not the adaptions, I found something startling. Some people were amazed that I enjoyed it so much — wasn’t it sexist? Racist? Simplistic?

Sometimes. You can’t take an author out of his time. If Howard had written with today’s political correctness in the 1930s, he couldn’t have made a living. Sure, a lot of the women are in Conan stories to be rescued (generally when Howard REALLY needed a sale), but there are strong female characters within his work, just as heroism can be found amongst many races within Howard’s stories.

Some of the plots are pretty simple, even if they are compelling, but much of Howard’s fiction has far more going on within than there would appear to be on the surface, which is part of its appeal. Mere mindless action would not have endured so long and still be capturing new fans, me among them.

You have to take Howard at his own terms, however. If you wander in expecting to find a trove of lit fiction or teenage vampire angst, or if you look with disdain upon tales of adventure, you’re apt to be disappointed. REH was ahead of his time in many ways, but he was a Texan writing for the pulp magazines in the early 1930s. Toss that in with his aforementioned youth before you take any issues with what you find in his prose.

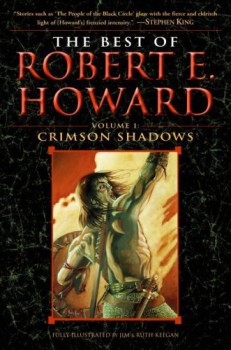

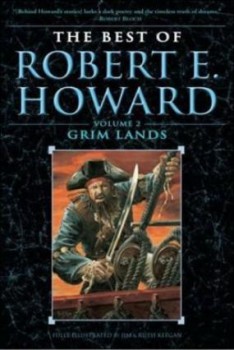

If you’re new to Howard, where can you find him? I suggest either volume of Del Rey’s Best of Robert E. Howard books, Crimson Shadows or Grim Lands. Try four or five stories out of there and see if you don’t notice what so many of the rest of us have seen. If you don’t, well, we all have different likes and dislikes. I won’t hold it against you.

If you’re new to Howard, where can you find him? I suggest either volume of Del Rey’s Best of Robert E. Howard books, Crimson Shadows or Grim Lands. Try four or five stories out of there and see if you don’t notice what so many of the rest of us have seen. If you don’t, well, we all have different likes and dislikes. I won’t hold it against you.

But if you DO see something you like, read on, because there’s more. A lot more. Those best of volumes aren’t like greatest hits collections of bands that had one good track per disc. That’s just a choice sampling, for there wasn’t nearly enough room in those best of volumes to get all the good stuff. No, if you like what you find when you stumble into the worlds of Robert E. Howard, you’ll have plenty to read for a long while, and much to revisit.

Not a year goes by that I don’t reread at least a handful of his yarns, reveling in a narrative power that still sweeps me up so fully that I stop noticing the words and fall between them, into the story.

In truth, I cannot single out the best thing or even the three best things in Robert E. Howard’s writing, but I name him one of my three favorite writers. Here’s to you, Bob. Today we celebrate the gifts you’ve left us. I wish that I might have thanked you in person for them. Since I cannot, I cherish your stories, and raise a toast to you in appreciation.

Reprinted from Black Gate online Jan 22, 2010

8 Comments