Swords Against Death Re-Read: “The Jewels in the Forest”

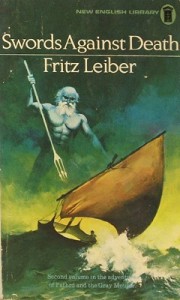

Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar series, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the second tale in the volume, “The Jewels in the Forest.”

Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar series, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the second tale in the volume, “The Jewels in the Forest.”

Howard: Coming upon “The Jewels in the Forest” for the first time in a quarter century was like sitting down at a warm campfire to hear a favorite tale. I recalled the gist of the events, but it didn’t keep me from enjoying the story all the way through. I was soon swept up into the adventure. It didn’t matter that I recalled the bones of the plot; the mystery beguiled me.

Even in this embryonic stage of his career Leiber was already displaying masterful touches, and it was wonderful to see. I paid especially close attention to the able way he did something today’s writers are told is taboo: he shifted between viewpoints whenever he damned well pleased, without chapter or section breaks of any kind. He usually accomplished this by showing us the character through the other’s eyes before the shift, like a director changing camera angles.

Bill: I was impressed by that as well, a few times I read back a ways to see how he made it work.

Howard: That’s exactly what I did! I was enjoying what he was doing so much I had to slow down and read deliberately to pay closer attention to the techniques. Even from the outset, Leiber does so many things right that I feel a little guilty about calling out a handful of things he does wrong, but – here goes.

He’s still getting his feet wet a little with his narrative, so when we encounter the two heroes for the first time we get a fairly static description of them rather than a sense of them in action, almost as though the frame has frozen in the camera. That said, Leiber’s prose is so smooth he carries it off. More awkward is the somewhat stilted dialogue between the characters in the opening segments. That, though, begins to ease by the halfway mark.

Bill: After that introduction he gives us a fun action scene that lets us know that these guys really know what they’re doing, ducking the arrows as they are launched, Fafhrd stringing his bow on horseback and loosing an arrow at their pursuers.

Bill: After that introduction he gives us a fun action scene that lets us know that these guys really know what they’re doing, ducking the arrows as they are launched, Fafhrd stringing his bow on horseback and loosing an arrow at their pursuers.

Howard: Absolutely. He might state flat out that they’re veterans, etc., but then he shows it. But (sigh) I said I’d discuss some flaws, so I’ll mention a few more before I get back to discussing all the great stuff. The arrival of the priest, something else I didn’t object to in my earlier readings, is extremely convenient to the story, almost like something you’d see in a stage play. It begs a little much from the reader.

Bill: The priest was the one thing that stood out to me as a flaw. Introducing him earlier, perhaps even as exposition (the mad priest that, for example, tried to take the “treasure riddle” from them earlier, or who the peasants noticed hanging around the area) would have removed his coming out of nowhere, without diminishing the mystery of who he was (at first I thought perhaps he was the old wizard who built the treasure house himself, as I think was Leiber’s intention). I do wonder if Leiber’s original idea was to give Lord Rannarsh the privilege of running ahead and getting his skull smashed in the treasure chamber, but he couldn’t resist a bit more swordplay and so gave him to the Mouser to dual.

Howard: I like your suggestions. My only other big issue with the tale was near the end. As a kid I was confused when I tried to envision the conclusion, probably because I’d never read anything like it before. Now I could picture everything clearly, apart from the fact it seems like Fafhrd twice leaps through the doorway to escape. I read that sequence multiple times, and I can only conclude the first doorway is an exit from an inner chamber and the second is the exit from the tower… but it’s just not clear.

Howard: I like your suggestions. My only other big issue with the tale was near the end. As a kid I was confused when I tried to envision the conclusion, probably because I’d never read anything like it before. Now I could picture everything clearly, apart from the fact it seems like Fafhrd twice leaps through the doorway to escape. I read that sequence multiple times, and I can only conclude the first doorway is an exit from an inner chamber and the second is the exit from the tower… but it’s just not clear.

Bill: Yes, the domelike inner, treasure chamber, and then the doorway at the bottom of the stairs to the tomb itself. I felt as if the layout could have been somewhat more concrete as well.

Howard: Everything else is nearly smooth as silk. The action sequences are spare and exciting in every instance. I particularly love the fight with Rannarsh’s men outside the tower, opening with Fafhrd and the Mouser nearly tricking them into retreat. It’s full of all sorts of wonderful precise details, like Fafhrd having trouble holding off two antagonists and knowing that holding off four is complete nonsense you’d only find in a saga. Or the Mouser’s sword suddenly dropping from the trees to land point first between Fafhrd’s attackers.

Bill: That was also one of my favorite parts. I felt the whole thing was both grounded in realism and yet also very fun and colorful. I remember being struck by the same thought the first time I read it, it stood out that much. Their reactions after the battle also reinforce the realism of the events — neither simply shrugs off the heightened emotions of a life and death struggle, but both have their own personal way of dealing with them.

Bill: That was also one of my favorite parts. I felt the whole thing was both grounded in realism and yet also very fun and colorful. I remember being struck by the same thought the first time I read it, it stood out that much. Their reactions after the battle also reinforce the realism of the events — neither simply shrugs off the heightened emotions of a life and death struggle, but both have their own personal way of dealing with them.

And grounding it all in realism is a great balance for, firstly, the weird nature of the mystery and the ending — I’m not a historian of the genre, but I can’t imagine the “tomb as monster” idea was too common when this story appeared. But also for the characters themselves, they are larger than life, they enjoy adventure for its own sake, they are arch and clever. But they aren’t superhuman in a fight, they aren’t immune to fear, and they don’t always succeed.

Howard: There also are excellent moments of character that any number of literary descendants could stand to pay better attention to (there are just enough, rather than too few, or two many, and it’s a fine line): the Mouser, worried by some presentiment about the tower, plays on Fafhrd’s fear of snakes to lure him out, although he has to be clever about it; Fafhrd weeping over the man he killed in a sword fight; Mouser’s concern for the girl’s safety even over his lust for treasure. (They’re rogues, but they’re not villains.) I could go on, but my portion of this analysis is getting long already.

Bill: Exactly. I loved that we got such a sense of who they were in the story, and not merely in a cliched or archetypal way. The two of them entertaining the peasants was another marvelous instance of characterization for both of them.

Bill: Exactly. I loved that we got such a sense of who they were in the story, and not merely in a cliched or archetypal way. The two of them entertaining the peasants was another marvelous instance of characterization for both of them.

And Leiber’s wonderful cleverness is on display throughout. I’ll end with my favorite quote, the Mouser nervously remarking on all the skeletons littering the stairs of the treasure house: “Our hosts are overly ancient and indecently naked.”

Howard: Oh yeah, great line. There are plenty of great lines, but then there are even more in later stories. I bet if we were to take a highlighter to a Leiber text every time we spotted a great bit of dialogue, nearly half of this book would be yellow.

While I’m sure you and I could go on, there’s only one more thing I’ll mention, and that’s the opening: “It was the Year of the Behemoth, the Month of the Hedgehog, The Day of the Toad. ” Apart from the animals different from ones Harold Lamb would have used, this sentence reminded me of the beginning to any number of his Cossack adventure stories. I wish I knew if Leiber had read the adventures of Khlit the Cossack. Leiber would have been very young when those Cossack tales were first printed. Unless there were old copies of Adventure magazine lying around the house it’s unlikely Leiber could lay hands on them, because they weren’t reprinted until long after “The Jewels in the Forest” saw publication. Still, when I went from Leiber to Lamb I found that the two writers shared some similarities. It may simply be that good adventure writers draw from the same well even if they aren’t familiar with each other’s works, or that both Lamb and Leiber were imitating a common source.

Next week we’ll look at one that was always one of my favorites, “Thieves’ House.”

9 Comments