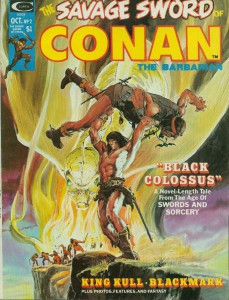

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “Black Colossus”

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Black Colossus.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Black Colossus.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: Maybe it’s not as deep, or as soulful, as some that are more routinely mentioned by Howard scholars, but this is one of my favorite Conan stories. This is the work of a master who knows exactly how far to push every moment, and understands exactly what his audience wants. Robert E. Howard is in complete control of this narrative from beginning to end.

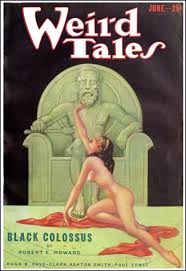

Look at that great opening, with its master thief and the tomb hung with menace. We witness the skill and capability of Shevatas, which makes it even more worrisome when it’s clear that he’s dead or worse by the segment’s end — an end that occurs off camera, to heighten suspense. And then, in section 2, we get Yasmela. REH was perfectly capable of showing us strong, independent women, but Yasemela isn’t really one of them. She’s a pampered princess in need of protection, but determined to help her nation… AND she’s gorgeous and prone to being naked. REH had to have known that red blooded heterosexual male readers would feel an instinctual desire for her, as well as a compulsion to protect her both from the creepy sorcerer and her other worries. We admire her pluck and courage and know that she needs someone (not us, though we might wish that) to rescue her. Yeah, she might not be real, but REH is playing us guys like a musician with a fiddle. He KNOWS the notes to hit to get the effect on us he likes.

Look at that great opening, with its master thief and the tomb hung with menace. We witness the skill and capability of Shevatas, which makes it even more worrisome when it’s clear that he’s dead or worse by the segment’s end — an end that occurs off camera, to heighten suspense. And then, in section 2, we get Yasmela. REH was perfectly capable of showing us strong, independent women, but Yasemela isn’t really one of them. She’s a pampered princess in need of protection, but determined to help her nation… AND she’s gorgeous and prone to being naked. REH had to have known that red blooded heterosexual male readers would feel an instinctual desire for her, as well as a compulsion to protect her both from the creepy sorcerer and her other worries. We admire her pluck and courage and know that she needs someone (not us, though we might wish that) to rescue her. Yeah, she might not be real, but REH is playing us guys like a musician with a fiddle. He KNOWS the notes to hit to get the effect on us he likes.

Bill: She’s an interesting parallel to Bêlit. Both are in positions of power, and both admire and rely on Conan because he is a cut above their own subjects. Yasmela has seen many strong men before in her capacity as ruler, but none such as Conan, whom she senses is no supplicant; he has never knelt before any man. Mitra certainly knows how to pick them!

Bill: She’s an interesting parallel to Bêlit. Both are in positions of power, and both admire and rely on Conan because he is a cut above their own subjects. Yasmela has seen many strong men before in her capacity as ruler, but none such as Conan, whom she senses is no supplicant; he has never knelt before any man. Mitra certainly knows how to pick them!

Howard: Man, does Conan enter in style this time, from stage right. The events are in motion, the pieces introduced, and then he’s there, larger than life and ready to wade into adventure. Well, first he’s ready to sweep Yasmela to bed, but once he sees what’s under way, he speaks plainly and wisely. There are so many great, simple lines here that reveal Conan’s character. I love how Conan talks tactics: “It’s no more than sword-play on a larger scale. You draw his guard, then – stab, slash! And either his head is off, or yours.”

Bill: And when Yasmela’s generals get their first look at him, he’s half-drunk and gnawing on a beef bone. From that great introduction onward the story really plays with the class and culture differences of the various players, until the final battle itself is a clash between salt-of-the-earth professional soldiers and a nobleman-led force under Nathok the Veiled One — the great Thugra Khotan, returned after three thousand years to have his vengeance on the descendants of the Hyborian hordes who crushed his old empire.

Bill: And when Yasmela’s generals get their first look at him, he’s half-drunk and gnawing on a beef bone. From that great introduction onward the story really plays with the class and culture differences of the various players, until the final battle itself is a clash between salt-of-the-earth professional soldiers and a nobleman-led force under Nathok the Veiled One — the great Thugra Khotan, returned after three thousand years to have his vengeance on the descendants of the Hyborian hordes who crushed his old empire.

Howard: Really good point. This is blue collar versus the upper crust. This isn’t a later generation’s “promised stable boy/forgotten prince.” Conan rises to lead because of his own skills and inborn traits.

Come chapter IV are some very fine mass battle scenes and descriptive passages of great excellence. Savor these lines that would cost hundred of thousands of dollars to film: “In the early haze of dawn the streets of Khoraja were thronged by crowds of people who watched the hosts frizzing from the southern gate. The army was on the move at last. There were the knights, gleaming in richly wrought plate-armor, colored plumes waving above their burnished sallets. Their steeds, caparisoned with silk, lacquered leather and gold buckles, caracoled and curvetted as their riders put them through their paces. The early light struck glints from lance points that rose like a forest above the array, their pennons flowing in the breeze.”

Come chapter IV are some very fine mass battle scenes and descriptive passages of great excellence. Savor these lines that would cost hundred of thousands of dollars to film: “In the early haze of dawn the streets of Khoraja were thronged by crowds of people who watched the hosts frizzing from the southern gate. The army was on the move at last. There were the knights, gleaming in richly wrought plate-armor, colored plumes waving above their burnished sallets. Their steeds, caparisoned with silk, lacquered leather and gold buckles, caracoled and curvetted as their riders put them through their paces. The early light struck glints from lance points that rose like a forest above the array, their pennons flowing in the breeze.”

Bill: And even more great word-painting when the battle itself occurs. That does remind me, though, of one thing I’ve never been crazy about in the Conan stories, and that’s the anachronistic technology in them. The french chivalric lexicon of armor pieces that is on display in this and some of the other stories (“they brought harness to replace Conan’s chain-mail — gorget, sollerets, cuirass, pauldrons, jambes, cuisses, and sallet.”) and some other anomalies like arbalests, is right out of the High Middle Ages, and just never feels right to me. Conan illustrators must agree, as I can’t recall ever seeing him in 15th century plate armor, indeed the Del Rey edition’s beautiful full page picture depicting the scene you quoted above, Howard, is distinctly bronze age Assyrian or Babylonian in character. It’s a minor criticism of something that never truly detracts from the story, and I will admit that in other respects certain anachronistic aspects of the Hyborian Age only add to its charm, but it does somewhat undermine my suspension of disbelief — I read those things and think more about REH’s influences than Conan’s world.

Howard: That’s something I notice but rarely pay much heed to. I guess I just gloss over the armor issue as I roll my eyes only a little at the reference to what sounds like age of sail ships in other Conan tales. The thing that does grate on me in Howard’s fiction is the occasional info dump/plot advancement through dialogue, even though I know that it was standard at the time. (I’ve read plenty of old fiction that does the same.) A lot of the time REH doesn’t lean on those techniques at all, so that when he does it really stands out. For instance, I’ve never much cared for the first story he wrote about Cormac Fitzgeoffrey because it’s weighted down with backstory through conversation that doesn’t sound remotely real. And yet within a little while after crafting it REH turned around and wrote some of the best historical fiction ever set to paper, completely free of any sort of hint of that.

Howard: That’s something I notice but rarely pay much heed to. I guess I just gloss over the armor issue as I roll my eyes only a little at the reference to what sounds like age of sail ships in other Conan tales. The thing that does grate on me in Howard’s fiction is the occasional info dump/plot advancement through dialogue, even though I know that it was standard at the time. (I’ve read plenty of old fiction that does the same.) A lot of the time REH doesn’t lean on those techniques at all, so that when he does it really stands out. For instance, I’ve never much cared for the first story he wrote about Cormac Fitzgeoffrey because it’s weighted down with backstory through conversation that doesn’t sound remotely real. And yet within a little while after crafting it REH turned around and wrote some of the best historical fiction ever set to paper, completely free of any sort of hint of that.

I suppose that we all come to fantasy fiction, or any fiction, really, with the ability to glory in some things and ignore others, and our enjoyment of one kind of genre depends in part upon what we can overlook. My wife and I enjoy a lot of the same sorts of stories, and I was both thrilled and surprised that she loved Harold Lamb’s tales of Khlit the Cossack. But she doesn’t care for Robert E. Howard in part because she finds the writing “purple.” Whereas I think REH at his finest is an incredible prose stylist. And I do think that Howard’s writing does appeal more to men than women, although such a broad brush comment shouldn’t be read as me saying that no women enjoy his work.

But I’ve drifted off topic. To return to “Black Colossus,” I think too often in fiction all the rulers and villains and principal characters are brilliant schemers. That’s just not as interesting from a sociological standpoint. Lots of history was made because people weren’t clever enough to make good choices. Student of history that he was, Robert E. Howard knew that battles hinged sometimes on poor or very human decisions. I love that the arrogant count Thespides, the knight, is more certain of victory depending upon his station and status than an actual knowledge of tactics, and I love that Yasmela, unschooled in warfare, thinks Conan in error for not supporting the count’s attack.

But I’ve drifted off topic. To return to “Black Colossus,” I think too often in fiction all the rulers and villains and principal characters are brilliant schemers. That’s just not as interesting from a sociological standpoint. Lots of history was made because people weren’t clever enough to make good choices. Student of history that he was, Robert E. Howard knew that battles hinged sometimes on poor or very human decisions. I love that the arrogant count Thespides, the knight, is more certain of victory depending upon his station and status than an actual knowledge of tactics, and I love that Yasmela, unschooled in warfare, thinks Conan in error for not supporting the count’s attack.

Bill: It’s wonderful stuff, as is the resultant exchange between Conan and his former mercenary commander, Amalric, who remarks that Thespides’ hot-headed charge is the sort of thing that Conan used to get up to. Conan agrees, but says that was when he was only worried about his own hide, now he’s responsible for others. Here Conan’s essential decency and honor feeds right into his maturation — this battle is his first command, and it’s really a freak of fortune that Conan is even in this position. But he’s smart, and he respects his fellow soldiers, having emerged just days before from their ranks himself, and all of that factors into him growing into a position of responsibility. Earlier, there is also reference to how kingly he looks all decked out in his new armor, something Conan would retain in the back of his mind for years. He’s growing as a character right before our eyes, a rather amazing thing considering these are stand-alone stories told in no particular order.

Howard: Oh yeah. I enjoy Amalric, and how we learn more about Conan through him. Again we see REH’s ability to give us a character for just a few brief scenes and make us fond of him — even though, if you peer behind the curtain, you can sort of see that Amalric’s real purpose is just to provide information or show us Conan in a different light. A lesser writer would have written him without managing to make us care about the character.

Bill: When we at last get to the climactic battle, it’s Conan’s patience, cunning, and cool that win the day. He stops a route of his hillman with his own raw presence, doesn’t commit to the battle when Thespides launches his foolish assault, and has the sense to risk a flank attack with Amalric when he sees that only a desperate move can bring victory. His counter-charge into the teeth of Nathok’s horde is done with makeshift cavalry — all the footman and mercs who never were themselves knights, hammering into a horde of aristocrats and their, possibly enchanted, slave soldiers. In the end, it’s ‘blue collar’ professionals led by a bone-gnawing pragmatist that route the proud charioteers and desert fanatics of the long-lost Sorceror-King.

Howard: It’s a textbook example of how to write mass battle sequences. Anyone wanting to write a battle scene with ancient or medieval armies needs to read this tale, or at least that final chapter. I think I could read it over and again and still be learning how its done.

My schedule precluded me from participating in any discussion this week, but I hope to drop by to see your own reactions to “Black Colossus” in the coming days. Next week, “Iron Shadows in the Moon.”

18 Comments