The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “Rogues in the House”

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Rogues in the House.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Rogues in the House.” We hope you’ll join in!

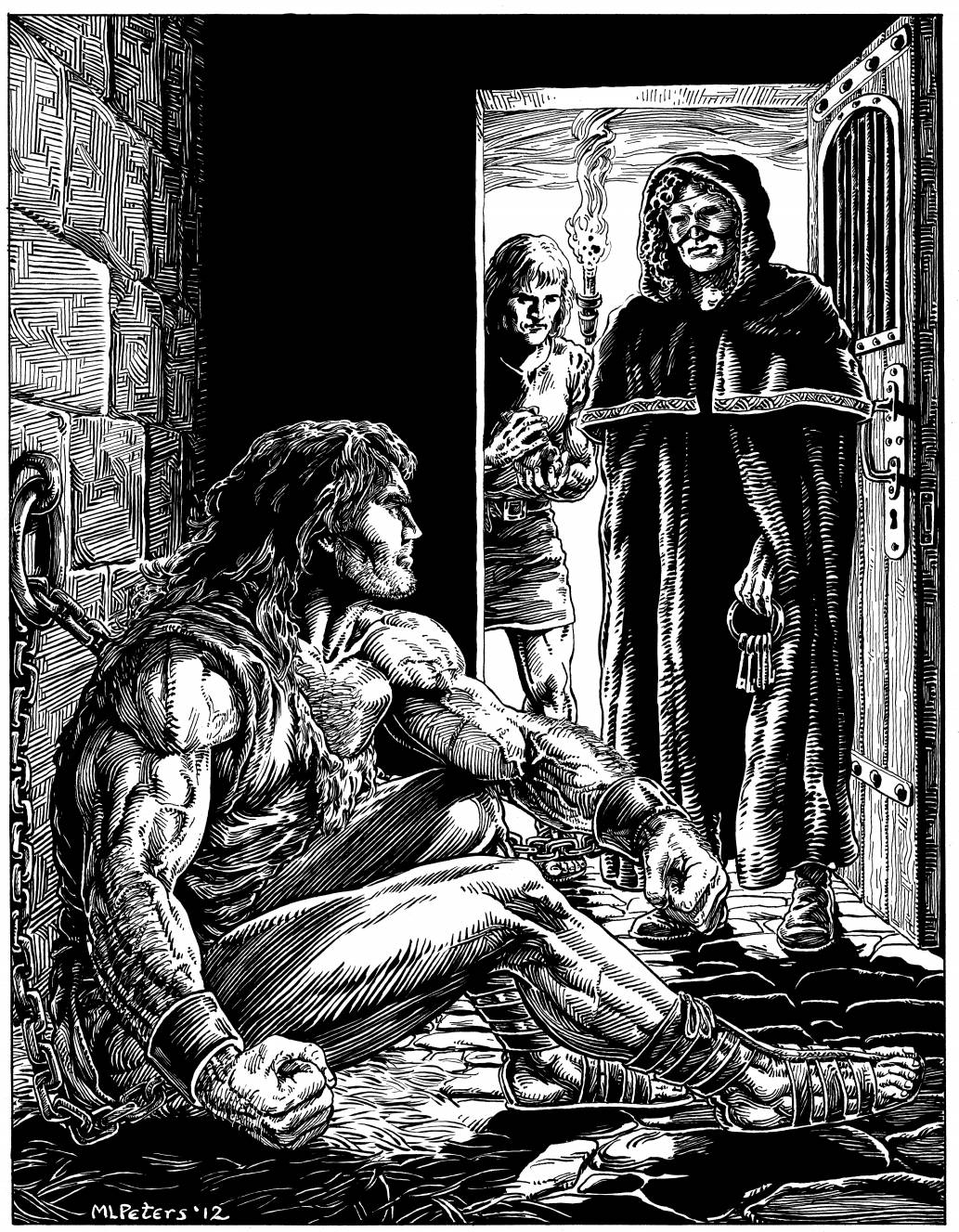

Bill: “Rogues in the House” is a welcome return to form after a few lesser Conan stories, and once again it sees Conan run afoul of civilization’s ways. The story reprises elements of “The God in the Bowl” and “The Tower of the Elephant” to give us Conan as a rogue and outlander — indeed the story begins with his incarceration for the murder of a priest. The priest in question was a thoroughly corrupt fence of stolen goods and police informer and, like the Red Priest at the center of this story or Kallian Publico or Yara from the aforementioned yarns, a prime example of the height of civilized hypocrisy and self-interest. A distrustful Conan says later in the story “When did a priest keep an oath?” and is proven correct in his distrust. The priestly class seems singled out as a prime exemplar of REH’s critique of civilized ways.

That conflict between barbarian and civilized man has been only a minor note in the last few stories, but in “Rogues in the House” it seems to inform everything. The story begins with the introduction of the Red Priest and the nobleman Murilo, the man that would get Conan into this adventure, in a very civilized, affected atmosphere. The threat made against Murilo is silent, unspoken, almost polite — its brutal image of a severed ear is housed, almost softened, by the decadent trappings of a golden box. Murilo, like his predecessor in “The God in the Bowl,” realizes he needs a stranger to dare the house of his priestly rival but, unlike in that earlier story, Murilo proves himself to be an honorable man, despite also qualifying as one of the “Rogues in the House” of the title.

Howard: Honorable in his personal dealings at least, but a traitor to his country! The story is so economical we never learn the reasons for Murilo’s selling state secrets, but we do see his personal bravery even in the face of danger, and he holds off trying to attack Thak — until he has a clear shot –for fear of hitting Conan. He’s a man of his word, so one wonders how he ends up as a traitor. It’s not really important to the tale, though. It’s a point of character complexity.

Howard: Honorable in his personal dealings at least, but a traitor to his country! The story is so economical we never learn the reasons for Murilo’s selling state secrets, but we do see his personal bravery even in the face of danger, and he holds off trying to attack Thak — until he has a clear shot –for fear of hitting Conan. He’s a man of his word, so one wonders how he ends up as a traitor. It’s not really important to the tale, though. It’s a point of character complexity.

Bill: We learn this early in the story, after Murilo’s plan to free Conan from prison goes awry, he himself goes to do the task he hired Conan to do — kill Nabonides, the Red Priest. That alone elevates him well above the schemer that betrayed Conan in “The God in the Bowl” and, once the Cimmerian joins him in the pits below the Red Priest’s abode, the two work well and honestly together to resolve the chaos storming around the Red Priest and his escaped creature, Thak the man-ape. Murilo might have perfumed locks (by which Conan’s heightened senses recognize him in the dark), but he’s also got courage and decency, two traits in short supply in REH’s civilized characters.

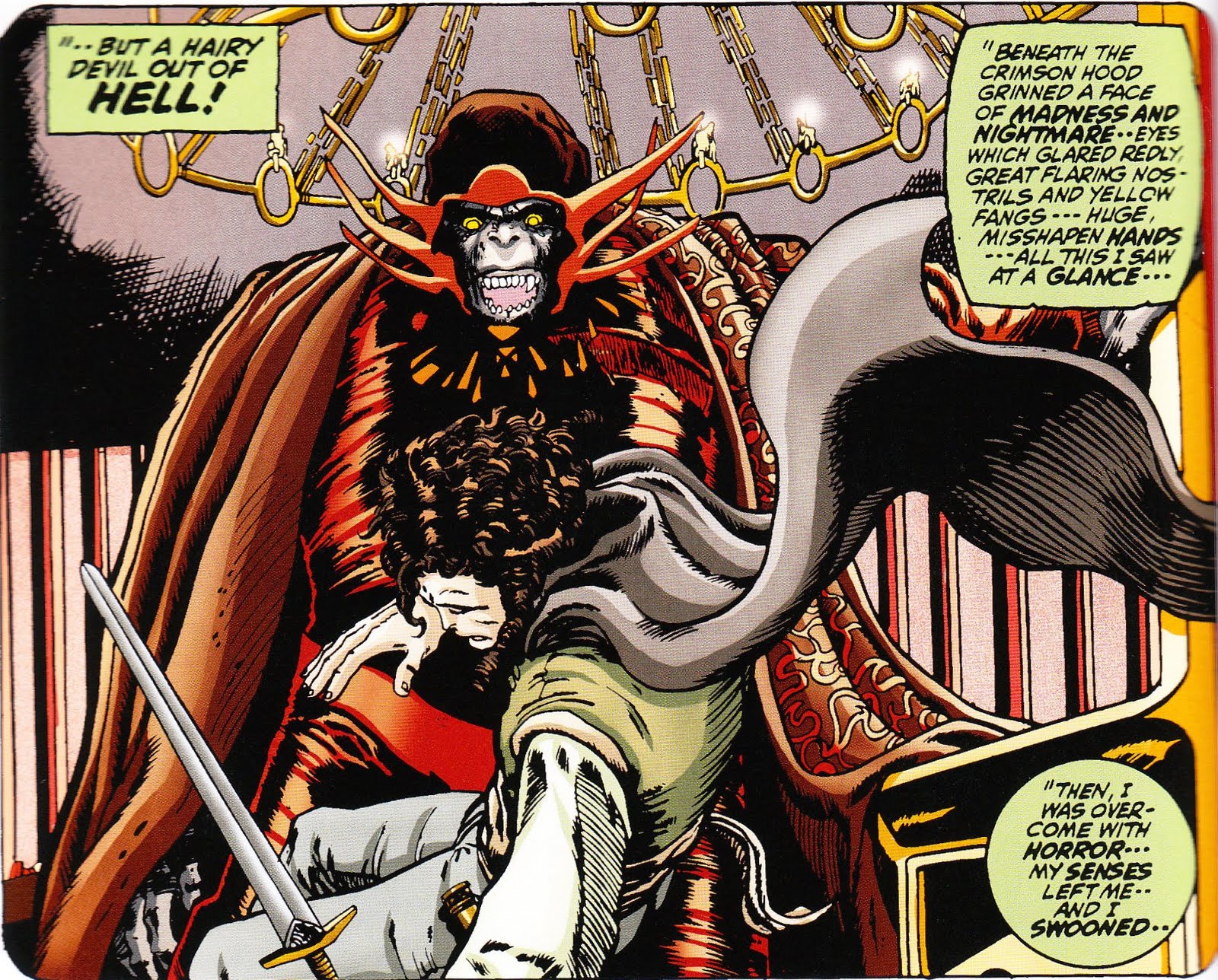

Howard: Very true. We can’t imagine Conan swooning at sight of the ape man, but Murilo does. We can’t imagine Murilo trying to jump on Thak’s back and wrestling him. Yet he’s brave and resourceful and honorable at a personal level. He is, in short, a decent civilized man, which allows a different juxtaposition from that we usually see between Conan and cultured people.

Howard: Very true. We can’t imagine Conan swooning at sight of the ape man, but Murilo does. We can’t imagine Murilo trying to jump on Thak’s back and wrestling him. Yet he’s brave and resourceful and honorable at a personal level. He is, in short, a decent civilized man, which allows a different juxtaposition from that we usually see between Conan and cultured people.

Bill: The Red Priest himself is one of the eponymous “rogues” of the title, a man described by Murilo as a plunderer and exploiter who sacrifices the future of his people for his own naked ambition. Indeed, Murilo cites Conan as the most honest rogue of them all, because he does what he does openly, even if it is theft and murder. Murilo and Conan are there to kill the Red Priest (and they aren’t the only ones!), but the three briefly join forces to survive the greater danger of the amok man-ape. In the end, of course, the treacherous priest betrays Conan and Murilo, though he adheres to the letter of their agreement and gleefully boasts of the technicality that allows him to keep his word — an oath made by a priest to the highest Hyborian god no less — just like you’d expect from a parasite of civilization.

The Red Priest is a manipulator, but he’s no magician like Yara. I thought it said interesting things about his character that he is a master of technology, that most civilized of things — his house is rigged with traps and he has a clever surveillance system that utilizes mirrors. Conan dismisses it all as witchery, but it is of course the opposite — what seems supernatural about the priest is really just more manipulation. This control extends even to living things, from the King of the city to lowly Thak, enslaved and abused man-ape of the far east.

Howard: And it’s strange that Murilo trusts him, but I suppose that points again to Murilo’s innate decency. And folly. He, unlike Conan, can’t really stand on his own. He doesn’t have the sense to trust his instincts. He’s right when he says Nabonides would never betray the oath he swore, but doesn’t reckon that the Red Priest will find another way to achieve his aim. Conan, more versed now to the kind of trickery that civilized man practices than he was in “The Tower of the Elephant,” doesn’t trust Nabonides no matter what he promises. He may not understand civilization, but he understands men and their behavior.

Howard: And it’s strange that Murilo trusts him, but I suppose that points again to Murilo’s innate decency. And folly. He, unlike Conan, can’t really stand on his own. He doesn’t have the sense to trust his instincts. He’s right when he says Nabonides would never betray the oath he swore, but doesn’t reckon that the Red Priest will find another way to achieve his aim. Conan, more versed now to the kind of trickery that civilized man practices than he was in “The Tower of the Elephant,” doesn’t trust Nabonides no matter what he promises. He may not understand civilization, but he understands men and their behavior.

Bill: If the Red Priest represents civilization at its worst, Thak is savagery at its most dangerous. It is no accident that the massive man-ape clads himself in the red mantle of his master. Certainly it allows for a brief moment of confusion as to what sort of were-sorceries the Red Priest gets up to, but much more to the point it shows a powerful innocent wholly corrupted by the civilization around him. Thak does nothing that his master has not already done, his simple imitative behavior is bloodthirsty, but it is learned. It is the Red Priest that has raised Thak to be a monster — a monster in his own image.

Howard: That’s a really good point, and one that isn’t stated explicitly in the plot. There’s more going on in these stories than is apparent from a simple surface reading, although it’s quite possible to just enjoy Conan tales as grand adventures.

Howard: That’s a really good point, and one that isn’t stated explicitly in the plot. There’s more going on in these stories than is apparent from a simple surface reading, although it’s quite possible to just enjoy Conan tales as grand adventures.

On re-reading it I was surprised that I haven’t visited this one more often. It gallops along. A lot happens in a short time because it’s told with such economy. And it’s very different from what has come before. I’ve been reading a lot of Conan pastiche in my downtime via The Savage Sword of Conan reprints recently, and so many of those writers model a Conan story off of the formula we saw in the last stories — monster, half-naked damsel, evil wizard/trap, escape. “Rogues in the House” breaks the formula and for this reason is even more of a pleasure.

Stepping back you can see how it’s a strange beast inspired from multiple sources — weird death traps out of Fu Manchu stories, a system of mirrors set to emulate a modern mastermind’s hidden cameras, and an ape servant who’s rebelled against his master. If someone had come and babbled the various story elements to me I would have rolled my eyes. Yet it works very well, in part because once it starts rolling it just never lets up.

You could say that about stories that catch you up and then realize upon re-examination that some of the elements didn’t make sense. That, however, can’t be said about “Rogues.” In retrospect it’s one fine scene after another, although my favorite moment may well be the conclusion.

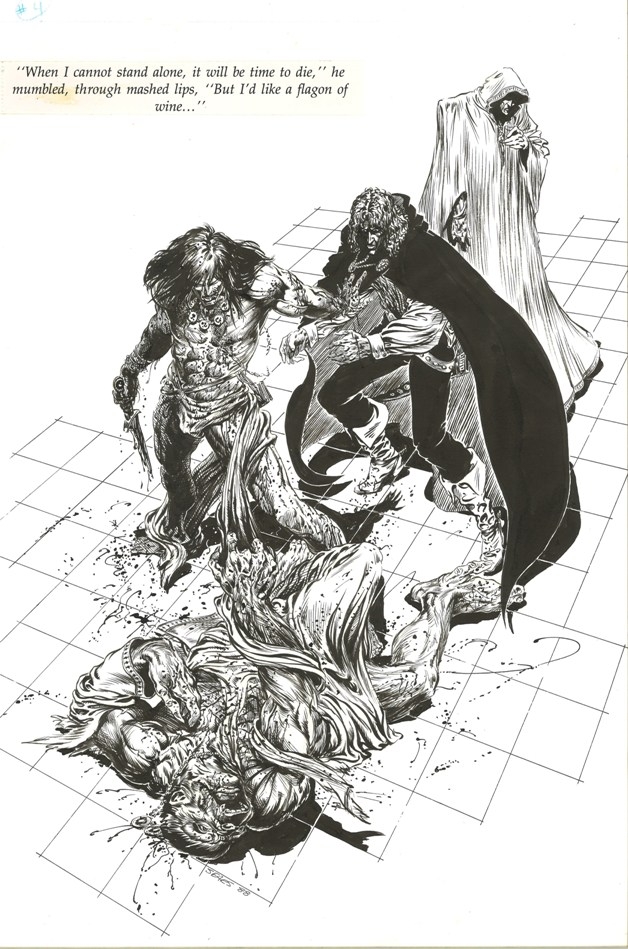

Bill: In the end Thak has an honorable death at the hands of a fellow outsider, and Conan honors his opponent by confirming that he was indeed a man, and a mighty one, and Conan’s victory over him is worthy of song. The Red Priest, on the other hand, gets his head bashed in by a thrown stool in mid-sentence. The contrast couldn’t be more clear, nor the meaning more eloquently expressed. One wonders if Conan himself couldn’t have turned out to be something like Thak had his life gone another way, or if his spirit had proven less indomitable.

Bill: In the end Thak has an honorable death at the hands of a fellow outsider, and Conan honors his opponent by confirming that he was indeed a man, and a mighty one, and Conan’s victory over him is worthy of song. The Red Priest, on the other hand, gets his head bashed in by a thrown stool in mid-sentence. The contrast couldn’t be more clear, nor the meaning more eloquently expressed. One wonders if Conan himself couldn’t have turned out to be something like Thak had his life gone another way, or if his spirit had proven less indomitable.

Howard: “His blood was red after all.” I love that. Anyone who thinks Conan has no sense of humor needs to take another look at these stories. He aims the traitorous woman for the cesspool to take his revenge, then laughs, and there’s this quip here… although Conan might simply have been making an observation. I’m inclined toward the former though, because Conan’s not so dense to believe that the red priest’s blood might be a different color, not based on the word of some rumor.

Bill: “Rogues in the House” does what the best Conan stories do, weaving character and theme together with strands of fierce adventure and sense of wonder, and I happily list it among my favorites.

Howard: I now list it among my favorites as well, and scratch my head a little that it wasn’t already there. Next week: “The Vale of Lost Women.” I’m not sure that Conan story’s a favorite of any fan. It’s one of the rejected Conan stories, found among Robert E. Howard’s papers long after his death.

10 Comments