The Fierce Impatient Side of Things

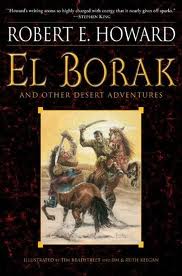

Lately I’ve been reading through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection El Borak And Other Desert Adventures. I’ve read a lot of these stories in various beat-up old paperbacks, but some are new to me, and others haven’t been read by me in ten years or so. As I’ve said elsewhere, Robert E. Howard was a vivid writer and brilliant crafter of action scenes. I love how swiftly he brings a scene to life, and how visual and cinematic his fight scenes are. I always learn something or catch some great turn of phrase whenever I’m reading his work, and I usually enjoy myself immensely.

Lately I’ve been reading through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection El Borak And Other Desert Adventures. I’ve read a lot of these stories in various beat-up old paperbacks, but some are new to me, and others haven’t been read by me in ten years or so. As I’ve said elsewhere, Robert E. Howard was a vivid writer and brilliant crafter of action scenes. I love how swiftly he brings a scene to life, and how visual and cinematic his fight scenes are. I always learn something or catch some great turn of phrase whenever I’m reading his work, and I usually enjoy myself immensely.

Sometimes I find myself growing annoyed with some of the artifacts of the era and magazine genre for which he wrote, particularly the racism, or the tendency for characters to infodump or villains to monologue. I know Robert E. Howard wasn’t himself a racist or sexist, but anyone who pales at seeing racism or sexism will be in for a rude awakening when they try out adventure fiction from the pulp era. Anyway, sometimes these aspects of the fiction that I otherwise quite enjoy start to irritate me… And then I think about how little I enjoy the sense of pacing in so many modern fantasy novels (how do people read such loooong books where nothing much happens for long stretches of time?) and how uninterested I am in novels that are mostly social criticism, and I remind myself how pleased I am to be reading some REH, who, like Conradin, seemed to celebrate the fierce, impatient side of things.

Conradin’s the protagonist in one of my very favorite short stories, “Sredni Vashtar,” penned by Saki, pseudonym of H.H. Munro. I think those critics who’ve turned up their noses at this very short story over the years missed its point. Perhaps they were never frustrated in their ambitions. It chiefly concerns a young boy whose older female cousin and guardian is determined to squash anything fun in his life for his own good, although I think it has more universal appeal. At this point, Saki is describing the ferret that Conradin has adopted and hidden from his cousin:

Conradin was dreadfully afraid of the lithe, sharp-fanged beast, but it was his most treasured possession. Its very presence in the tool-shed was a secret and fearful joy, to be kept scrupulously from the knowledge of the Woman, as he privately dubbed his cousin. And one day, out of Heaven knows what material, he spun the beast a wonderful name, and from that moment it grew into a god and a religion. The Woman indulged in religion once a week at a church near by, and took Conradin with her, but to him the church service was an alien rite in the House of Rimmon. Every Thursday, in the dim and musty silence of the tool-shed, he worshiped with mystic and elaborate ceremonial before the wooden hutch where dwelt Sredni Vashtar, the great ferret. Red flowers in their season and scarlet berries in the winter-time were offered at his shrine, for he was a god who laid some special stress on the fierce impatient side of things, as opposed to the Woman’s religion, which, as far as Conradin could observe, went to great lengths in the contrary direction.

Saki manages to say so much, so efficiently. His command of prose is masterful. I revisit his best stories regularly.

But more often I visit Robert E. Howard. And here, to represent the fierce, impatient side of things, is Francis Xavier Gordon, aka El Borak, from “Three-Bladed Doom” (p. 134 of the aforementioned book).

Thrown into confusion by the unexpected blast which mowed down three men and set others to staggering and crying out, the Arabs fell into demoralized confusion. Some fired wildly at the Sikh, some at Gordon as he charged them, and all missed, as is inevitable when men’s attention is divided. And as they fired futilely Gordon was among them with a rush and a gigantic bound. His dripping blade spattered blood and left a wake of writhing, dripping figures behind him — then he was through the milling mob and racing down the corridor, shouting for Lal Singh as he headed to pass the corridor door of the adjoining chamber from which the Sikh had fired.

Bloody and graphic, but also economical. We don’t see each sword strike, we just receive the impression of the moment, the headlong pace. Howard knows when to power us forward through the scene. THIS isn’t even the important battle. He’ll make sure to slow things down when El Borak finally faces off against the head villain.

Anyone wanting to write good action scenes ought to be visiting and re-visiting Robert E. Howard and taking plentiful notes. While it’s true there are other fine action writers to crib notes from, anyone curious about how best to depict a conflict portraying the movements of an entire regiment or army would be hard pressed to find someone as skilled as REH, who used his typewriter like a skillful cinematographer to show us all the crucial bits AND keep up the pacing. None of those dark unsteady camera angles for him. It’s all crystal clear, and it doesn’t dwell on the unimportant.

7 Comments