Dialogue Cheats

I was sending some advice along to a young writer friend last night, and I thought (I hope) that it might be of use to other writers, so I’m pasting it below.

I was sending some advice along to a young writer friend last night, and I thought (I hope) that it might be of use to other writers, so I’m pasting it below.

I suppose I should make clear that I’m not one of those writers who feels you can only use “said” to indicate when someone is speaking, or that you have to avoid using adjectives with “said.” Sometimes I run across reviews that criticize an author for employing descriptive modifiers to “said.” I find that kind of criticism misguided.

I understand that almost any writing technique used to excess can be ridiculous, and this avoidance of using anything apart from said probably stems from having read fiction that’s tortuously laden with adjectives. (Have you ever read those books where the writer goes so far out of the way to NOT use said that it’s cringe inducing?). Using ONLY said isn’t the fix, though. It’s like killing the patient to stop the disease. Said isn’t completely invisible, and leaning only upon it is likewise overuse. A writer should use every trick he or she has to convey their story.

With that preamble out of the way, here are some dialogue cheats.

There are great shortcuts you can use when someone’s speaking. In a back and forth exchange where you’ve already introduced the two characters involved, if someone asks a question and someone else answers, you don’t need to identify both of them with named dialogue tags.

There are great shortcuts you can use when someone’s speaking. In a back and forth exchange where you’ve already introduced the two characters involved, if someone asks a question and someone else answers, you don’t need to identify both of them with named dialogue tags.

For instance, if Kirk and Spock are patrolling together for the lasagna monster:

Kirk pivoted and raised his phaser. “Spock, did you see that?”

“I saw, Captain, but I did not understand.”

Note two things. First, I don’t have to say Kirk asked, or Kirk shouted. Because it’s part of the same paragraph where I described Kirk’s action, I don’t even have to mention him speaking. The reader can assume the speech came from the character who just moved.

Note two things. First, I don’t have to say Kirk asked, or Kirk shouted. Because it’s part of the same paragraph where I described Kirk’s action, I don’t even have to mention him speaking. The reader can assume the speech came from the character who just moved.

Second, because Kirk’s asking Spock a question, we, the reader, know that it’s Spock answering and you, the writer, don’t need to indicate it. You could also do this:

The first officer arched an eyebrow. “I saw, Captain, but I did not understand.”

Now we’ve added an action, but we still haven’t used a dialogue tag.

Please understand that I’m not at all suggesting you should STOP using dialogue tags, I’m just showing you a way to mix things up so that sometimes you can use them and sometimes you can indicate who’s talking without using them.

Here’s another dialogue tip. Some writers have several spoken sentences in a row before the speaker or even the speaker’s tone is indicated. You can break that up to avoid confusion. Your reader’s thinking: who’s speaking? Oh, yeah, now I see. If you go too long without indicating who’s talking it pulls the reader out of the story, something you want to avoid. Keep things moving smoothly.

Here’s another dialogue tip. Some writers have several spoken sentences in a row before the speaker or even the speaker’s tone is indicated. You can break that up to avoid confusion. Your reader’s thinking: who’s speaking? Oh, yeah, now I see. If you go too long without indicating who’s talking it pulls the reader out of the story, something you want to avoid. Keep things moving smoothly.

Here’s an example of too many sentences in a row without identifying the speaker:

“Don’t you think I know that? There was, but not anymore! They called me, they begged me for help, four hundred of them! I couldn’t, I… I couldn’t…” Decker said, sobbing.

Watch what happens when I write the dialogue this way:

“Don’t you think I know that?” Decker cried. “There was, but not anymore! They called me, they begged me for help, four hundred of them!” His hands shook and his voice faltered. “I couldn’t, I… couldn’t…”

“Don’t you think I know that?” Decker cried. “There was, but not anymore! They called me, they begged me for help, four hundred of them!” His hands shook and his voice faltered. “I couldn’t, I… couldn’t…”

It’s perfectly acceptable to break up the dialogue by indicating the speaker after the first sentence and then continuing. You can break in as many times as you want… although you should be careful, too, because it’s very, very easy to overdo a technique and use it too much.

Lastly, some writers use a weird construction that drives me crazy. They’ll make anything a dialogue tag. For instance:

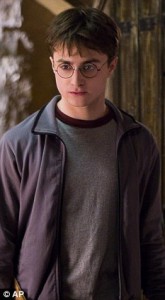

“I don’t like that,” Harry frowned.

“I don’t like that,” Harry frowned.

Well, you can’t really FROWN a line of speech. Frowning doesn’t produce a noise, like shouting, or sobbing, or saying. You could write:

“I don’t like that,” Harry said, frowning.

Or:

“I don’t like that.” Harry frowned.

That last one is subtly but importantly different from the first example. Because there’s a period and not a comma after “that” it’s clear Harry is speaking, and frowning, as an action, but that you, the writer, don’t think frowning actually produces sound. This may just be my own personal preference, because I’ve seen some very famous writers ignore this rule, and it hasn’t stopped them from selling books. Still, I think it looks weird the more you think about it. Illogical, an old mentor of mine would say.

2 Comments